The U.S. federal government is rapidly investing in emergent technologies to surveil migrants, residents, and citizens alike. What began as physical border monitoring has expanded beyond drones, surveillance towers, and ground sensors to include software systems that analyze social media activity, phone and text communications, biometric identifiers, and large-scale behavioral data.

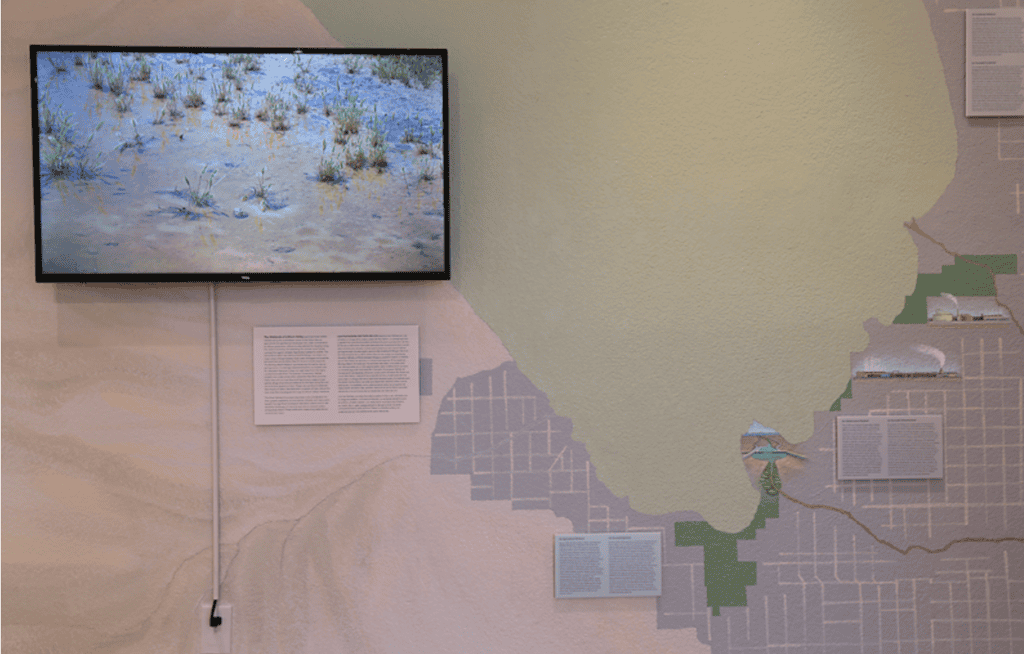

This expansion coincides with an intensification of physical surveillance infrastructure along the U.S.–Mexico border. Small aerial drones now conduct routine patrols over border regions, extending surveillance into remote and previously inaccessible terrain. Autonomous surveillance towers equipped with radar, thermal imaging, and high-resolution cameras maintain constant observation across vast stretches of land, while ground-based sensors in the landscape detect footsteps, vehicle movement, and vibrations. At official ports of entry, biometric systems collect facial and iris data from travelers, further integrating the physical body into immigration enforcement databases. Recent reporting has underscored how these material interventions increasingly function as tools of deterrence themselves, including proposals to modify the border wall’s surface and thermal properties—such as painting it black to increase heat exposure—as part of an expanded enforcement strategy.

Palantir has become indispensable to these efforts. The data analytics firm was recently awarded a $30 million federal contract to develop ImmigrationOS, a platform that aggregates information from passport records, Social Security files, IRS tax data, and license-plate reader databases to assist agents in identifying and prioritizing individuals for deportation. ImmigrationOS relies on algorithmic risk assessment to determine which cases should be pursued first, raising critical questions about how such systems define “risk.” Investigative reporting in 2016 demonstrated that automated law-enforcement decision tools routinely replicate existing racial bias, disproportionately labeling Black defendants as high-risk compared to white defendants—a pattern that is likely to reemerge in immigration enforcement contexts.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement has also dramatically expanded its use of digital surveillance tools capable of extracting the full contents of personal smartphones, scraping social media histories, mapping location data purchased from data brokers, and intercepting cellular communications. These tools have been used against not only undocumented immigrants, but asylum seekers, visa holders, permanent residents, and U.S. citizens alike. In this way, immigration enforcement functions as a testing ground for surveillance technologies that are increasingly normalized and redeployed across the broader population.

This expansion, however, is not confined to the borderlands, as CBP’s jurisdiction extends 100 miles into the interior of the United States from any land or maritime border, where two-thirds of the U.S. population resides. CBP operates a nationwide surveillance program that analyzes license-plate reader data to track millions of drivers, flagging supposedly suspicious travel patterns deep into the interior of the United States, and subjecting these drivers to traffic stops, interviews, and searches. Through this, the border (meta)physically expands beyond the fixed geographic line.

The ease with which personal data is harvested, analyzed, and sold—coupled with advances in AI technologies—has helped establish a contemporary panoptic system in which constitutional protections erode under the weight of physical and digital surveillance regimes. Within this system, individuals’ purported potential for criminality is continuously assessed and assigned by automated processes accountable to neither their subjects nor meaningful public oversight.

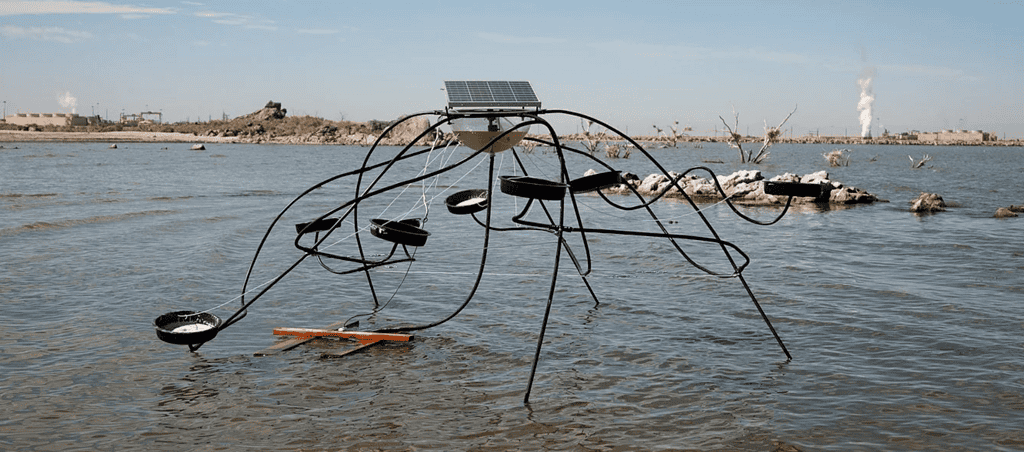

Case Study: Electronic Disturbance Theater 3.0, Social Echologies: Scene 3 (from Three Echologies: An Á/Area//Aria X Play)

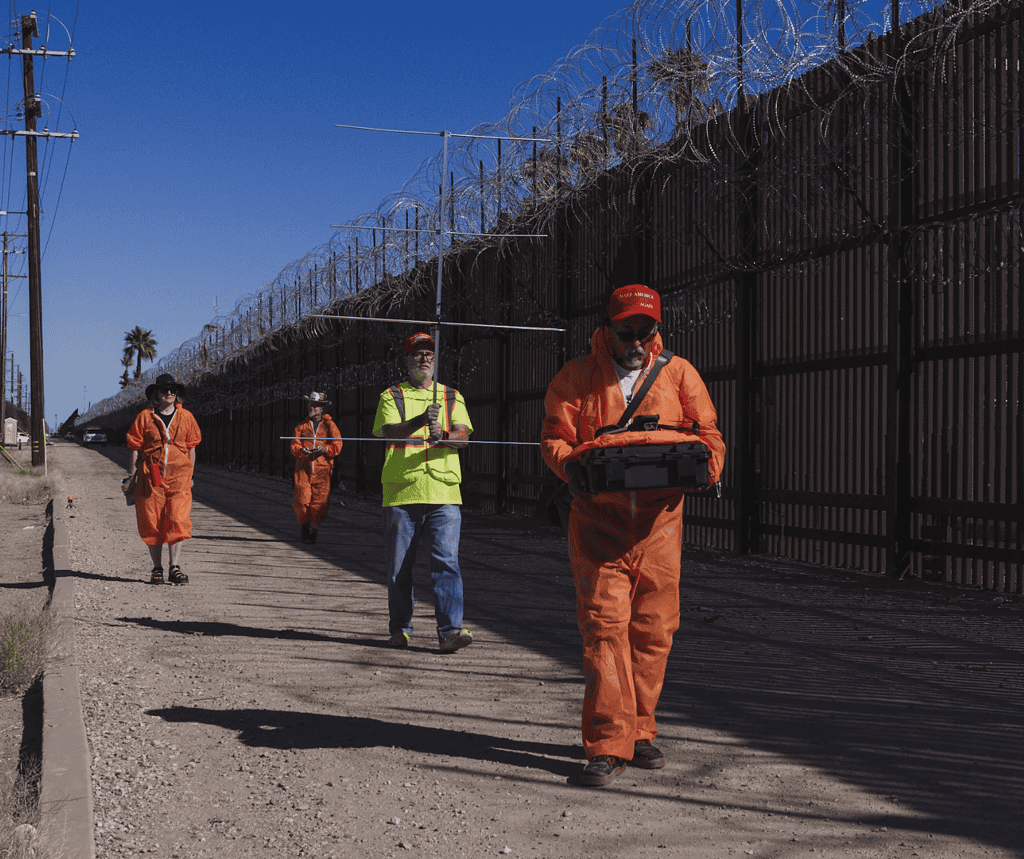

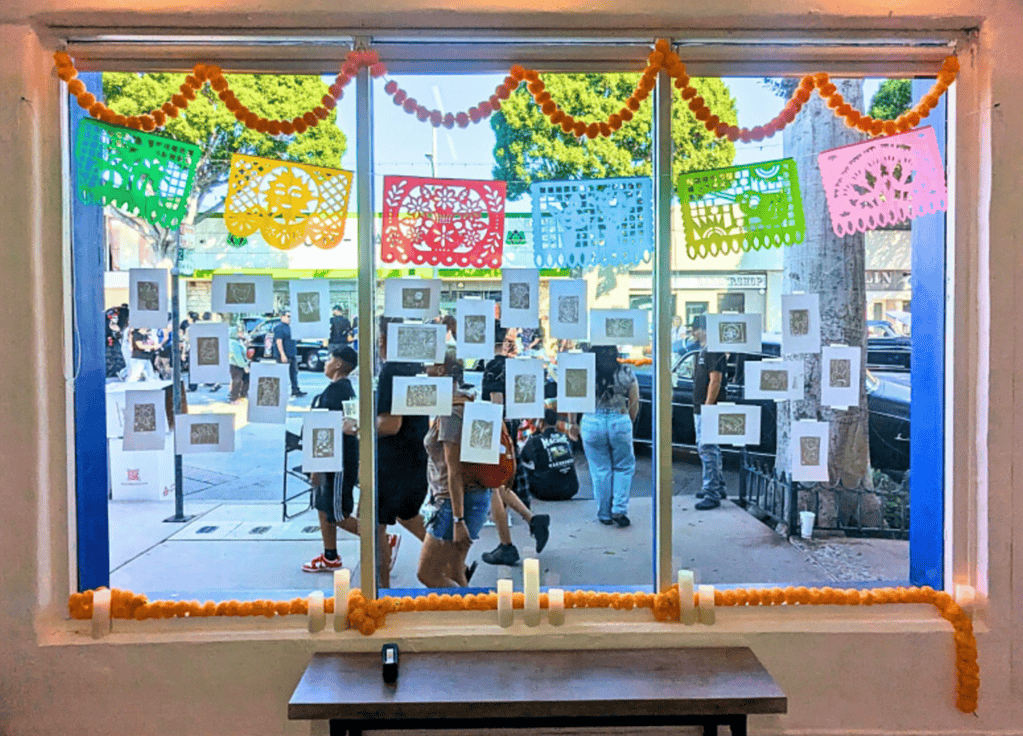

Electronic Disturbance Theater 3.0 (E.D.T.) staged a performance-happening at the Calexico–Mexicali border wall titled Social Echologies: Scene 3 (from Three Echologies: An Á/Area//Aria X Play). The artist collective had staged the two scenes that preceded this one in San Diego and Mexico City, respectively. Wearing red “MAKE AMERICA GREATER MEXICO AGAIN” hats and orange hazmat suits, half of the collective was positioned on the Calexico side of the border, the other half in Mexicali, a configuration that resembled past Biennial performances. Two performers spoke into microphones connected to bluetooth speakers suspended from two remote-controlled miniature drones, the performers’ voices variously in/audible against the dynamic sounds of queuing cars, vendadores, and a street busker along the Mexicali side. The drones were “palindrones,” rasquache replicas of Predator drones, the remotely piloted aircraft used by the U.S. Air Force for reconnaissance and combat in wars around the world. The performance was transmitted through two antennae, one on each side of the border, creating an interface between the play’s local broadcast on radio and the “a(e) ria(l)” disturbance of the palindrones searching out, chasing, and “singing” this scene of the play to U.S. Homeland Security. This “echolocating” sound gesture summoned subaltern knowledge of past, present, and future farmworkers, migrant laborers, and Zapatistas in an area reconfigured as “X.” During the performance, neither palindrone breached the border, but the one on the U.S. side mysteriously crashed, or was shot down, as U.S. border patrol and Mexicali police lurked behind the scenes.

E.D.T.’s use of palindrones stages an inversion of surveillance technologies, appropriating and subverting the very means of aerial sensing, signal transmission, and target recognition by which Homeland Security maintains the border and identifies targets for detention and removal. The slogan emblazoned on the collective’s hats refers to U.S. land seizure from Mexico in the nineteenth century, while also confronting the colonial logics that continue to underwrite U.S. interventionism. The performance-happening assumes heightened significance amidst renewed federal claims that military incursions into Mexico are necessary to disempower cartel networks, reinscribing the United States’ self-proclaimed role as the police force of the Western Hemisphere. Against this backdrop, the performance’s transmission operates as an active interference within hegemonic media narratives that normalize and justify such interventionist policies and operations.

Resources for further study:

"Ana Muñiz: The Specter of Surveillance in the Borderlands". Paranormal Borders Podcast, March 28, 2025. https://mexicalibiennial.org/ana-muniz-the-specter-of-surveillance-in-the-borderlands/

The discussion centers on how the border has become increasingly militarized and surveilled following NAFTA and 9/11 through the implementation of digital surveillance systems. Criminologist Ana Muñiz analyzes the ways in which these digital, disembodied mechanisms of control become embodied through their facilitating of cross-border flows of capital while simultaneously restricting physical migration. Muñiz also describes racialized state violence as a form of haunting, wherein the threat of incarceration and deportation constantly lurks in the shadows of the mind.

Muñiz, Ana. Borderland Circuitry: Immigration Surveillance in the United States and Beyond. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

Image: Electronic Disturbance Theater 3.0, Social Echologies: Scene 3 (from Three Echologies: An Á/Area//Aria X Play), 2023. Drone and poetry border activation. MexiCali Biennial: Land of Milk & Honey.

Paranormal belief plays an often overlooked adaptive role in human psychological and cultural life. Beliefs help individuals and communities navigate uncertainty, maintain emotional equilibrium, and construct meaning in environments where traditional systems of support have eroded. Research in the psychology of religion shows that humans are naturally inclined to interpret unusual experiences through supernatural frames because such interpretations offer comfort, coherence, and agency. When confronted with the unpredictable—loss, trauma, ecological disaster, or social isolation—the paranormal allows people to transform chaos into story and fear into symbolism.

The theory of bounded affinity suggests that humans across cultures share a natural affinity for encounters with the “super-empirical”—visions, intuitions, apparitions, synchronicities, altered states—but that organized religions create boundaries determining which of these experiences are accepted as legitimate (miracles, divine intervention, prophecy) and which are dismissed as illegitimate (ghosts, telepathy, hauntings, UFO encounters, psychic perception). Religious and paranormal encounters arise from the same fundamental human capacities for awe, intuition, and engagement with the “super-empirical.” The difference lies not in the experiences themselves, but in how institutions draw boundaries around what is considered sacred or legitimate. This means the paranormal acts as a culturally flexible spirituality, allowing people to access meaning beyond the constraints of traditional religion. In borderlands—where Catholicism, Indigenous cosmologies, folk practices, and modern mysticism intersect—these boundaries become especially porous, enabling hybrid forms of belief that support emotional resilience and communal identity.

In a time marked by loneliness, disconnection, and declining institutional trust, paranormal belief can provide belonging, narrative structure, and a sense of participation in something larger than oneself. Rather than a symptom of fear, it can be a creative, restorative practice—a way to re-enchant the world, reconnect with community, and assert purpose in places where the normal has failed to offer stability or care. Through this lens, the paranormal becomes not a fringe phenomenon, but a vital human strategy for adaptation and survival.

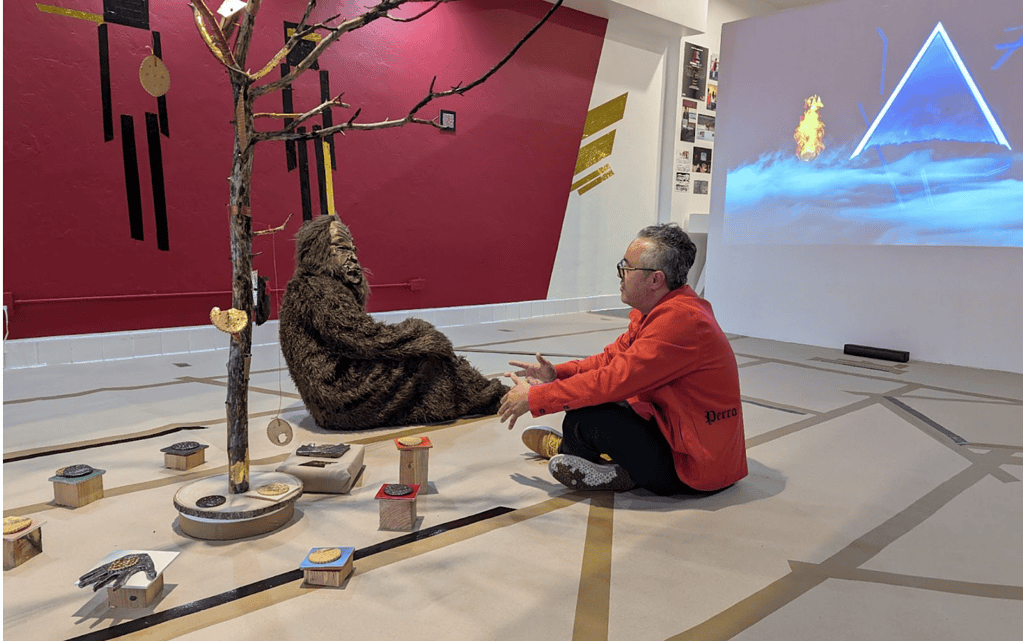

Case Study: Ismael Castro, El Lupón

In El Lupón, Mexicali-based artist Ismael Castro fabricates a border saint whose presence emerges not from institutional canonization but from collective need. Lupón exists through an altar along the border, a circulating statuette held by devotees, a prayer, a corrido, a dance, and a growing body of oral stories. As a saint of migrants, Lupón offers protection, accompaniment, and meaning where legal systems, religious institutions, and state protections repeatedly fail.

Crucially, Lupón occupies the porous space between religion, folklore, and the paranormal. He draws on Catholic saint traditions while refusing ecclesiastical legitimacy, aligning instead with folk spirituality and border myth-making. This hybridity exemplifies how paranormal belief operates as a flexible spiritual technology—one that allows individuals to generate meaning without requiring institutional validation. In this way, El Lupón is not simply an artwork or myth, but a coping infrastructure: a shared narrative that absorbs fear, redistributes hope, and reclaims agency in a borderland where the normal has long ceased to provide care.

El Lupón was part of the inaugural MexiCali Biennial in 2006 in which Ismael Castro painted a temporary mural and built an altar to the figure on the wall of Chavez Studios in East L.A. Learn more about Lupón HERE.

Image: Ismael Castro, El Lupón. Mural

American culture is steeped in an inherited colonial worldview that sees catastrophe as imminent, purity as necessary, and moral vigilance as a civic duty. This remnant of Puritan Doomsdayism framed the world as a battlefield between good and evil, purity and contamination—an apocalyptic mindset that has migrated seamlessly into the modern cultural landscape. One need only recall the recent social-media chaos surrounding the falsely predicted Rapture of 2025, a supposed cleansing of the Earth that turned TikTok into a frantic arena of earnest believers and rapid-fire parody. In this section, we draw from a new wave of writers, journalists, and podcasts that connect these cultish patterns of thought to contemporary political unrest.

These modern movements exemplify connections to this older theological ideology:

The MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) initiative echoes Puritan fears of bodily and moral corruption, turning health into a spiritualized marker of virtue.

Christian nationalism revives the Puritan belief in America as a divine project under siege, weaponizing apocalyptic language to justify exclusion and control.

White supremacy mirrors Puritan anxieties about “degeneration” and “racial purity,” projecting a mythic past that must be defended at all costs.

ICE raids in the 100-mile border zone enact a form of Puritan surveillance—the belief that the state must be ever-watchful, righteous, and unrestrained when confronting perceived impurity or threat. The disappearance of migrants echoes the Puritan notion that certain bodies can be morally erased for the preservation of the “elect.”

QAnon extends Puritan Doomsdayism into the digital age, casting political conflict as an apocalyptic struggle between hidden evil and a chosen remnant. Its prophecies, secret knowledge, and salvation narratives revive Puritan fears of corruption and spiritual warfare, transforming conspiracy into a modern form of religious purity politics.

The Seven Mountains Mandate carries Puritan ideas of divine national destiny into the present, framing political power as a form of spiritual warfare. Its call for Christian control over government, media, and education revives Puritan purity politics and apocalyptic fears, reinforcing Christian nationalism as a contemporary expression of colonial theology. These concepts also surface—though in a more secular manner—within the structure and goals of Project 2025.

This haunted political atmosphere conveys a metaphysics of precarity that blurs theological, political, and paranormal fears. It offers a genealogy of the politics of fear as a distinctly American supernatural logic.

Case Study: Ed Gomez, Four Horsemen

In January 2025, Ed Gomez exhibited a collection of work titled Sacred Disruption

for the PARA/normal Borders Lab. This show—a minor survey of Gomez’s broader art practice—highlighted themes of the sacred and the universal through imagery of space exploration, extraterrestrial presence, and apocalyptic myth. Shown here is a painting from Gomez’s Horsemen series, which consists of four life-size works, each offering a contemporary interpretation of the Four Horsemen from the Book of Revelation.

Sacred Disruption curator Armando Pulido notes that the “figures recall recent collective action against police brutality, forced deportations, exploitative labor practices, and international struggles against oppressive surveillance states. Though some of these figures appear benign, Gómez invites us to question just who might be at the helm of the Pale Horse’s destructive forces—and whether there is any chance to correct the course of accelerated collapse and confrontation.”

Image: Ed Gomez, Four Horseman #1 Conquest, 2015. Oil on Canvas.

“For disappearance is a state-sponsored method for producing ghosts, whose haunting effects trace the borders of a society’s unconscious. It is a form of power, or maleficent magic, that is specifically designed to break down the distinctions between visibility and invisibility, certainty and doubt, life and death that we normally use to sustain an ongoing and more or less dependable existence.” - Avery F. Gordon

In Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, sociologist Avery F. Gordon writes about desaparecido (disappearance) as a kind of ghost-making—a deliberate act by those in power to create shadows where people once stood. To disappear someone is not only to remove a body; it is to carve a hole in the social world, a wound that refuses to heal. The vanished hover at the edges of everyday life: in the empty chair at dinner, the phone that never rings, the name whispered with uncertainty. Their absence becomes a presence. A haunting.

This logic was clear in Latin America’s darkest decades, when military regimes in Argentina and Chile perfected the art of erasing people without a trace. Men, women, students, union organizers were taken suddenly, without witnesses, without acknowledgment. Families searched morgues, police stations, hospitals, churches, and military bases, often encountering nothing but denial. The uncertainty was the point. You cannot mourn what the state refuses to admit is gone. Instead, you live inside the ache, the not-knowing, the sense that at any moment another person could simply—vanish.

Disappearance becomes a message: We can reach anyone.

It becomes a lesson: Stay in line.

It becomes a haunting: The state is everywhere, even where you cannot see it.

Today, this same logic echoes across the U.S. ICE agents appear without warning—outside a grocery store, during a routine traffic stop, at a bus station, inside a courtyard, at dawn on the doorstep. Someone is taken, often without explanation, often without the ability to contact family. People do not know if their loved one is in a county jail, a private detention center, a transport van, or already across the border. Mothers call hotlines. Fathers search detention databases that never list the right names. Children go to school not knowing if their parents will be home when they return.

This uncertainty does the state’s work.

Fear flows through neighborhoods long after the agents leave.

Absence haunts.

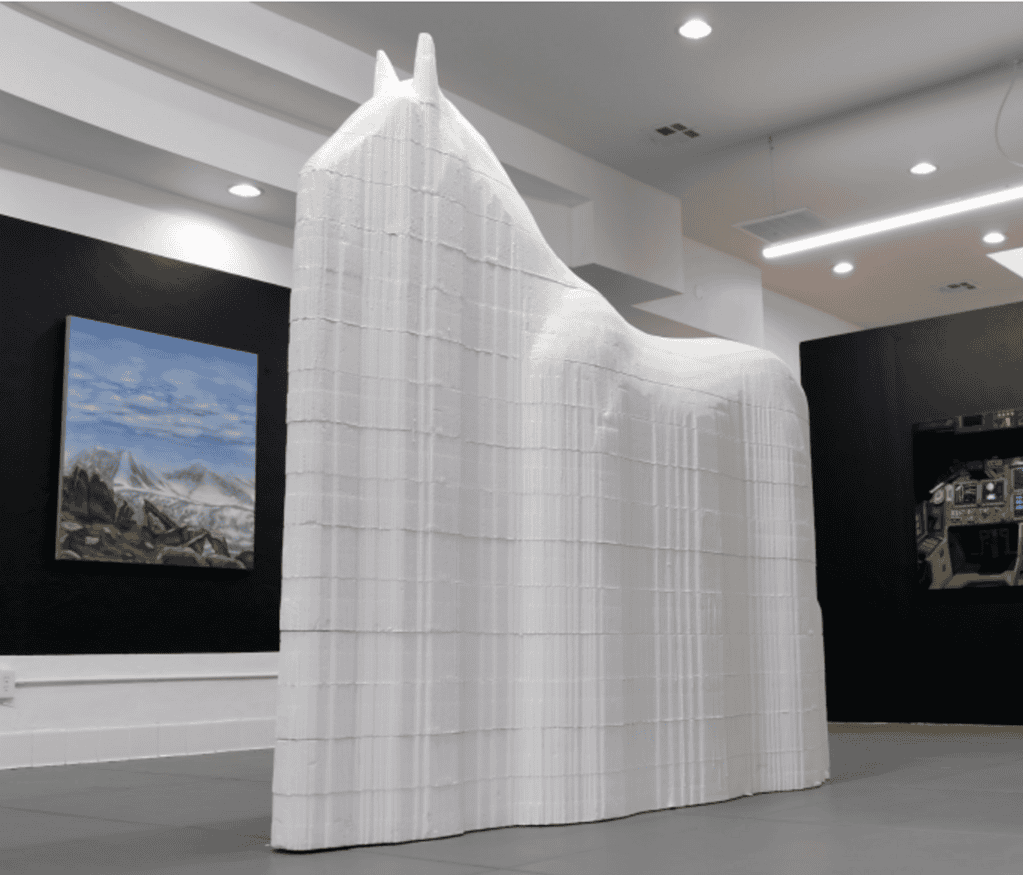

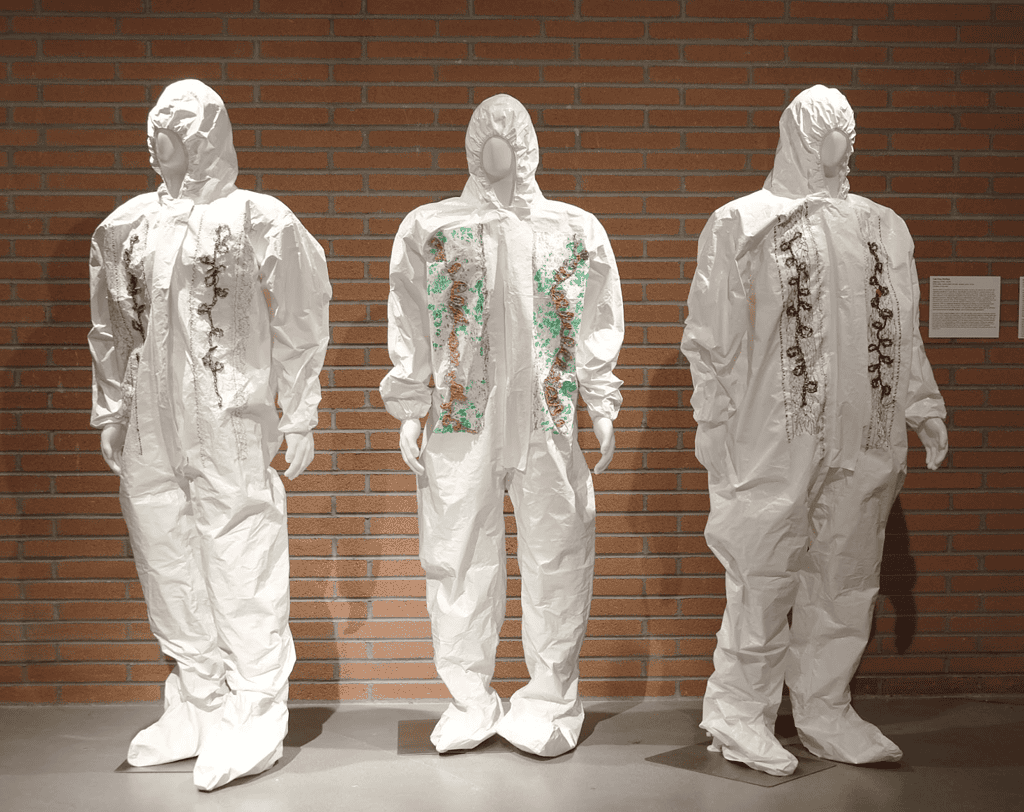

Case Study: María José Crespo, Screen Memories

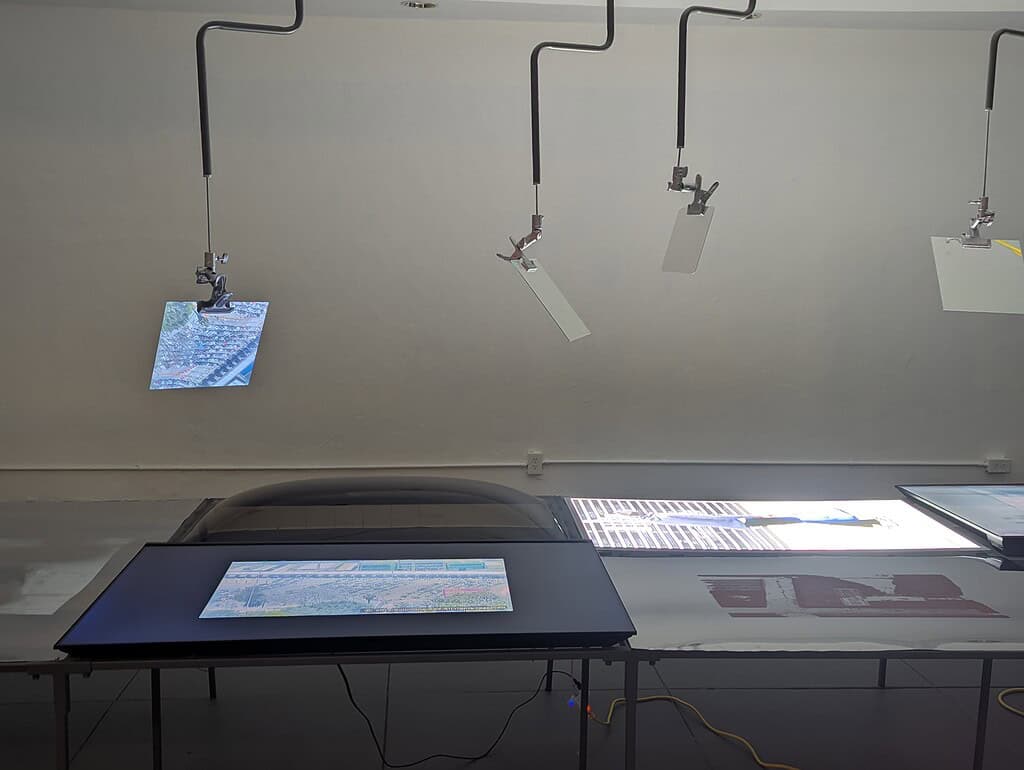

María José Crespo’s Screen Memories offers a powerful counter-map to disappearance. In the installation, ghosts lead the viewer into a speculative data center—an imagined archive built from fragments that are normally hidden, discarded, or denied. Drawing on years of footage collected from a Police WhatsApp group, Crespo layers rearview images of Tijuana’s alleys onto teleprompter glass, creating a spectral interface where official and informal archives collide. Here, the city becomes a haunted zone saturated with hypervisibility and systemic forgetting, shaped by visas, biometric checkpoints, and technologies of control that cannot fully contain what they seek to regulate. In Screen Memories, ghosts—understood as social figures—move through fractured timelines and failed surveillance systems, reanimating the traces of those who have slipped beyond the frame. This exhibition was part of the PARA/normal Borders Lab and was curated by Rosela del Bosque. Curatorial text and documentation can be found HERE.

For Further Research:

"Ana Muñiz: The Specter of Surveillance in the Borderlands". Paranormal Borders Podcast, March 28, 2025. https://mexicalibiennial.org/ana-muniz-the-specter-of-surveillance-in-the-borderlands/

The discussion centers on how the border has become increasingly militarized and surveilled following NAFTA and 9/11 through the implementation of digital surveillance systems. Criminologist Ana Muñiz analyzes the ways in which these digital, disembodied mechanisms of control become embodied through their facilitating of cross-border flows of capital while simultaneously restricting physical migration. Muñiz also describes racialized state violence as a form of haunting, wherein the threat of incarceration and deportation constantly lurks in the shadows of the mind.

Image: María José Crespo. Screen Memories, 2025. Mixed media sculpture.

Conspiracy theories and paranormal beliefs often appear to belong to separate worlds—one political, the other supernatural—but research increasingly shows that they share a deep psychological and cultural architecture. Both arise in moments of uncertainty, and institutional distrust. Both provide alternative systems of meaning when official narratives feel incomplete or inaccessible. And both thrive in liminal spaces—geographical, emotional, and epistemological—where people stand at the edge of the known world.

Studies describing Rabbit Hole Syndrome highlight how conspiracy belief develops not through sudden conversion but through gradual immersion: accidental curiosity becomes recursive engagement, which eventually becomes an all-encompassing worldview. This process mirrors the way people descend into paranormal interpretive worlds, where each uncanny event, synchronicity, or anomaly deepens the sense that there is “more” beneath the surface. Conspiracy and paranormal thinking both offer what researchers describe as self-sealing realities: systems where each new piece of information reinforces, rather than destabilizes, belief.

Such systems flourish when trust in institutions falters. Research on conspiracy beliefs and science rejection reveals that communities often turn toward conspiratorial or supernatural explanations when scientific or governmental authority feels opaque, contradictory, or hostile. Science’s inherent uncertainty—its revisions, debates, and disclaimers—can mirror the instability experienced in marginalized communities, especially those living within the 100-mile border zone where the law itself becomes flexible, exceptional, and unpredictable. Here, both paranormal sightings and government conspiracies become ways of explaining a world where the rules shift without warning.

Beyond distrust, conspiracy beliefs also fulfill psychological needs. Studies on the psychological benefits of conspiracy theories show that these narratives restore a sense of meaning, identity, and personal significance. They provide the thrill of hidden knowledge and the ego-protection of believing one is part of a perceptive minority. Paranormal belief performs similar functions: it offers forms of wonder, connection, and self-worth that resist rational reduction. The difference lies primarily in emotional tone—paranormal beliefs often offer enchantment, while conspiratorial beliefs more often cultivate fear and distrust.

Historical trauma provides another layer. Research shows that conspiracy theories can function as adaptive responses to collective wounds: colonization, displacement, war, racial violence, and systemic erasure. Border communities, shaped by centuries of geopolitical rupture, policing, and forced movement, often experience these ruptures somatically and spiritually. Paranormal encounters—ghosts, apparitions, curses, desert lights, unexplained presences—become ways of narrating histories that official archives refuse. Conspiracies emerge from the same wound: explanations that name the forces otherwise left invisible.

Network analysis further confirms the overlap: paranormal belief and conspiracy belief share cognitive traits such as magical thinking, pattern-seeking, and heightened sensitivity to anomalies. Yet their emotional outcomes diverge. Paranormal belief can enhance wellbeing when tied to healthy self-esteem and meaning-making; conspiracy belief is more often linked to negative affect, distrust, and dissatisfaction. In the borderlands, these two systems interweave, creating a distinct epistemology of survival—one where supernatural encounters and political suspicion operate as parallel strategies for interpreting an unstable world.

Together, these findings reveal that conspiracy and paranormal belief are not aberrations but adaptive cultural tools. In the borderlands—where state power is diffuse, histories are ruptured, and reality feels intrinsically porous—they become parallel forms of knowledge, offering coherence in a landscape defined by uncertainty.

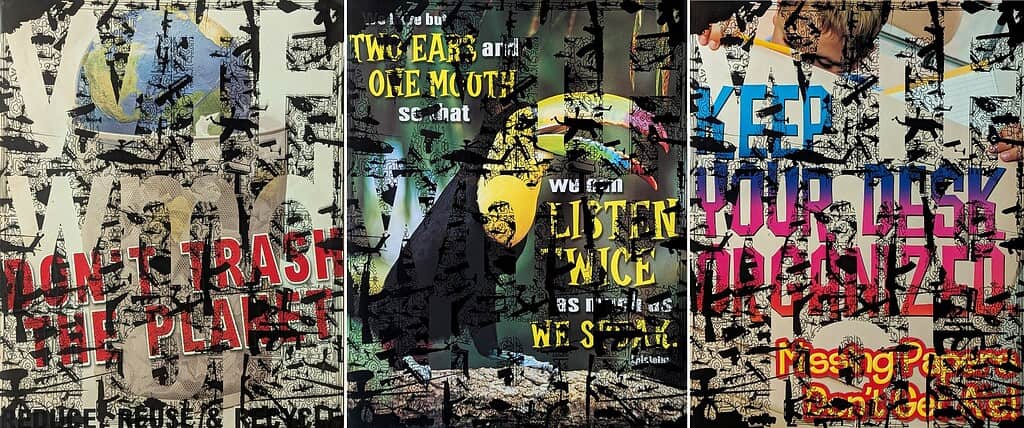

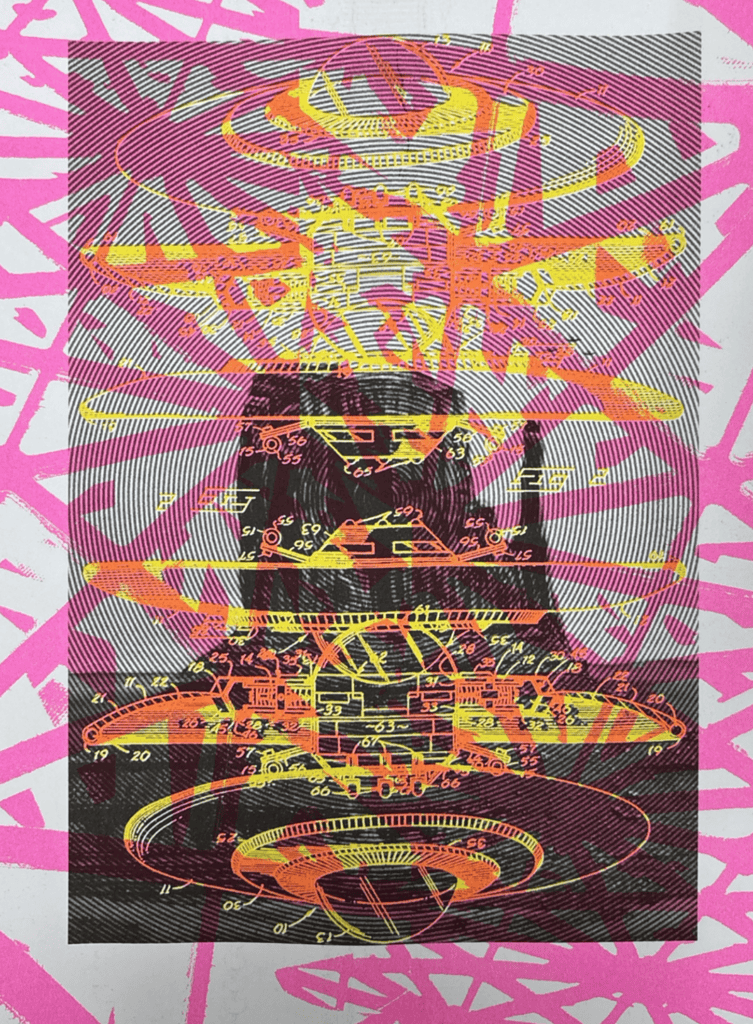

Case Study: Ed Gómez, WTF / WMD / LOL

In this body of work, Ed Gómez examines how conspiracy thinking is cultivated not through fringe belief, but through everyday systems of education, media, and visual repetition. Beginning in 2010, Gómez repurposed mass-produced educational posters—objects designed to deliver simplified facts, moral lessons, and motivational slogans to young audiences. Rather than encouraging inquiry, these posters model rote absorption, training viewers to accept information quickly and uncritically.

Gómez disrupts this logic by layering modular screenprinted forms onto the posters and encoding them with the acronyms “WTF,” “WMD,” and “LOL.” These signals mirror the language of contemporary media culture, where meaning is reduced to shorthand and emotional reaction. “WMD,” in particular, references the Weapons of Mass Destruction narrative used to justify the U.S. invasion of Iraq—an emblem of how misinformation, fear, and authority converge. The recurring presence of Apache helicopters reinforces the visual language of militarized power and surveillance.

The work operates as a slow-reveal system: its critique emerges only through sustained attention. In doing so, Gómez exposes how conspiratorial logic and state propaganda share a common architecture—both rely on repetition and emotional conditioning. Positioned within a mass of images and messages, the posters visualize how paranoia, compliance, and belief are manufactured, normalized, and embedded into everyday life.

This work was part of Sacred Disruption at MXCL BNL LAB for the PARA/normal Borders Lab. A photo essay of the exhibition with a curatorial overview by Armando Pulido can be found HERE.

Find a comprehensive list of academic studies that support the mirroring of conspiracy theories and paranormal beliefs on the downloadable PARA/normal Borders Overview.

Image: Ed Gomez. WMD, WTF, LOL, 2010. Offset print on educational posters

Conspirituality describes the convergence of New Age spiritualism with conspiracy-driven political ideology. The recent emergence of automated algorithms on social media sites has generated a massive increase in this phenomenon, especially as the creators of these sites reward accounts that drive engagement through controversy. Coined by scholars Charlotte Ward and David Voas, the term helps explain how online communities blend wellness culture, apocalyptic prophecy, and distrust of institutions into a coherent worldview that attracts large digital audiences. Narratives about corrupt global elites, once confined to fringe online forums, have become mainstream, as seen in the ascent of QAnon after the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

As healthcare and housing prices soar in the U.S., further entrenching existing structures of economic inequality, legitimate frustration with the ability of political and corporate elites to evade taxation, regulation, and criminal prosecution provides fertile ground for skepticism and disillusionment. Bad-faith actors, however, often redirect this widespread distrust toward marginalized groups through myths like the white supremacist “great replacement” theory, or toward government-backed scientific institutions like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These conspiratorial narratives align closely with white Christian nationalist movements and echo older historical precedents. Scholars such as Jules Evans have traced parallels between today’s far-right spiritual currents and earlier esoteric and anti-scientific movements, including those that flourished in Nazi Germany. Contemporary figures, such as U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services RFK Jr., have further amplified this blend of alternative medicine, patriarchal spiritual rhetoric, and anti-institutional sentiment under the slogan "Make America Healthy Again."

The rapid spread of misinformation within this digital ecosystem intensifies existing distrust in governmental and scientific institutions, granting conspiratorial influencers both legitimacy and mass visibility. Journalist Anne Applebaum describes this broader cultural shift as New Obscurantism: a climate of fear, suspicion, and anti-intellectualism that erodes democratic discourse. In this environment, evidence-based debate becomes increasingly difficult, allowing charismatic actors to deepen public polarization and weaken collective trust in institutions, and in one another.

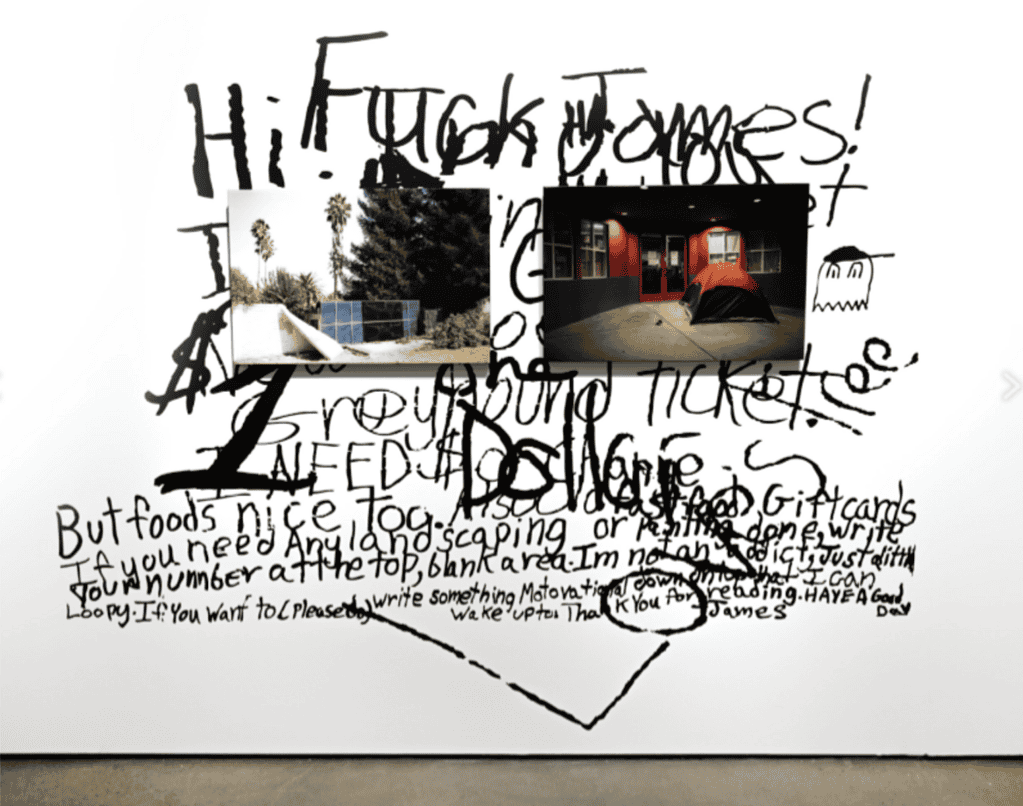

Case Study: Julio Romero, Silicon Valley XX, Silicon Valley XIV, and Gracias por leer

Julio Romero's multimedia installation is composed of two digital photographs, Silicon Valley XX (2015) and Silicon Valley XIV (2014), set against Gracias por leer (2015), which consists of black text scribbled onto the gallery wall. While Silicon Valley XX depicts a site of urban refuse amidst a sunny sky and rows of palm trees, Silicon Valley XIV captures a tent—likely a makeshift domicile belonging to an unhoused person—in front of the closed entrance to a building at night. The ironic inclusion of "Silicon Valley" in the title of both photographs refers to the unprecedented accumulation of capital in tech industries occurring alongside a cost of living crisis in California that threatens economic precarity for members of the working class. For Gracias por leer, Romero frantically scribbled pleas for work, declarations of his sobriety, and a request for a Greyhound bus ticket, all of which are ubiquitous on signs held up at traffic stops and intersections by those experiencing homelessness.

Ironically, social media sites become the primary spaces in which disillusioned and disenfranchised members of the proletariat share their existential fears regarding the encroachment of tech and AI into all facets of life, as well as the conspiracy theories that provide alternative means of quelling economic and spiritual anxieties.

This work was exhibited as part of the MexiCali Biennial's 2018-19 program CALAFIA: Manifesting the Terrestrial Paradise exhibition at the Robert and Frances Fullerton Museum of Art in San Bernardino, CA. Find more HERE.

Image: Julio Romero, Silicon Valley XX and Silicon Valley XIV, 2015. Archival pigment encapsulated in resin. Thank You For Reading, 2015. Site-specific installation using text obtained from found objects.

A state of fear and suspicion - the shadow side of knowledge.

PARA/noia identifies conspiracy and supernatural belief as cultural symptoms that address intersecting existential fears. These largely stem from the erosion of material well-being, an unprecedented rise in the cost of living, the degradation of social trust, political corruption, militarization of borders, and rapid technological innovation. As political and economic institutions fail to address these vulnerabilities and as social media algorithms accelerate social atomization and political polarization, individuals increasingly seek out alternative frameworks of explanation — often conspiracy theories or supernatural beliefs — to make sense of their worlds, to regain a sense of control over their lives, and to alleviate anxiety.

At the same time, however, PARA/noia also differentiates between belief as a tactic of coping and belief as a means of exerting control. The research included here demonstrates that conspiracy thinking arises from repetitive exposure to ideas that then calcify into closed belief systems. These belief systems allow the individual to dismiss evidence that opposes their perspectives and to redirect the frustration stemming from the resultant cognitive dissonance towards marginalized and scapegoated communities.

The algorithmic architectures of social media enable this tendency by placing users in rhetorical echo chambers that further solidify belief through exposure to more misinformation and like-minded others. In the current political climate, disinformation brokers, far-right movement leaders, and the state are weaponizing this distrust to normalize and legitimate authoritarian rule.

PARA/noia (para: beyond; noos: mind) explores how fear becomes knowledge, who profits from the cultivation of distrust, and whether subversive ideological frameworks can be used to cultivate collective meaning rather than enforce control.

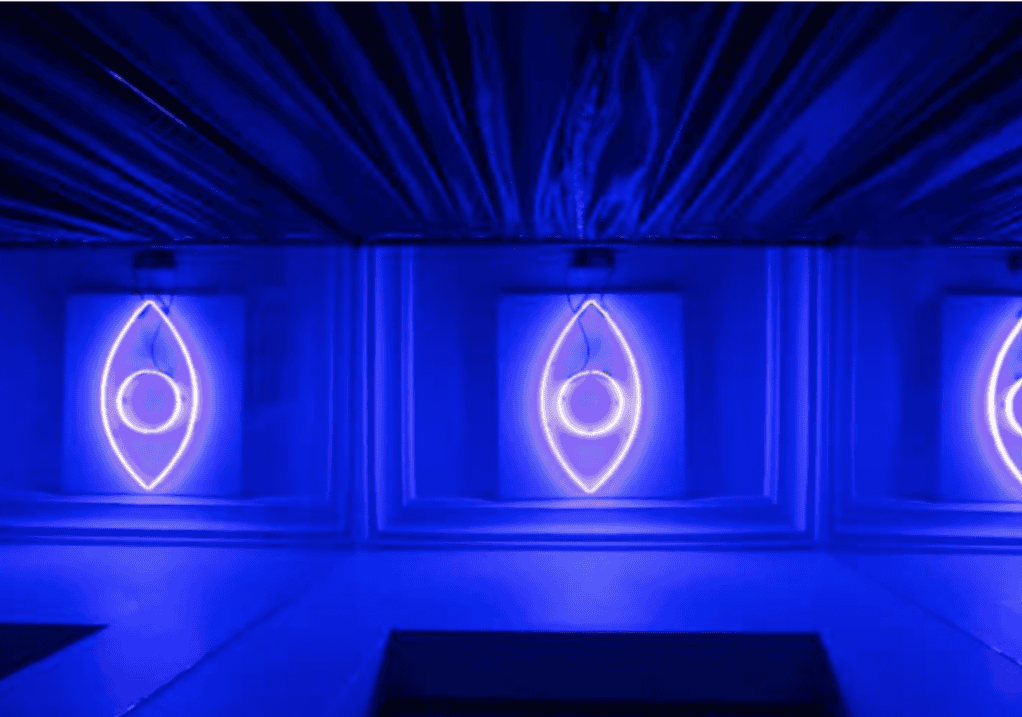

Image: Sergio Bromberg, Checkpoint with stainless steel, 2012. Stainless steel, electrical cords, retina scanner. MexiCali Biennial 2013: Cannibalism in the New World at Vincent Price Art Museum.

Mind beyond itself; consciousness crossing physical boundaries.

The PARA/psychology section examines states of consciousness that appear to exceed or destabilize conventional boundaries of perception, embodiment, and selfhood, drawing from interdisciplinary research in (para)psychology, neuroscience, and cultural studies. This framework approaches phenomena such as trance, dissociation, near-death experiences, and other forms of anomalous perception as empirically observed experiential patterns that recur across cultural and historical contexts. Clinical and experimental research suggests that altered states—whether induced by ritual practice, physiological stress, sensory deprivation, focused attention, or collective ceremony—can generate consistent perceptual, cognitive, and emotional effects, including shifts in spatial awareness, time perception, memory integration, and self–other boundaries.

Within this framework, artistic practices engaging dreamwork, trance, and visionary experience are understood as modes of inquiry that translate interior, often ineffable states into material form, opening portals to worlds both within and beyond the self. At the same time, PARA/psychology critically attends to the institutional histories through which such states have been classified, extracted, or pathologized. More recently, these industries have demonstrated an interest in integrating Indigenous knowledge systems into existing healthcare infrastructures; however, such efforts frequently replicate extractive dynamics, incorporating techniques while subverting the authority of Indigenous healers and detaching spiritual practices from the cosmologies and communities that sustain them. In response, collaborative models led by Indigenous communities emphasize consent, reciprocity, and self-determination, ensuring that integration occurs through partnership rather than extraction, and that spiritual authority, cultural continuity, and decision-making power remain with Indigenous practitioners.

Accordingly, this node acknowledges the limits and controversies of parapsychological research, emphasizing methodological rigor and skepticism while remaining attentive to how altered states challenge dominant epistemologies of consciousness. It foregrounds Indigenous spirit medicine and cosmologies as enduring frameworks for understanding mind, body, land, and relationality. PARA/psychology thus explores how consciousness is shaped by uncertainty, trauma, imagination, and power, and how integrating Indigenous-led approaches into broader healthcare and research practices can support cultural continuity, ethical care, and collective well-being without reproducing histories of colonial extraction.

Image: Guillermo Estrada, Almendroides, 2025. Glazed ceramic. Part of Almendroides, Almendroides, Aliens & Indígenas

Throughout the Americas, Indigenous practices for maintaining health and attaining emotional well-being often rely on the ceremonial use of sacred plants sourced directly from the land. These ritualized, often communal practices stand in marked contrast to the widespread reliance of psychiatric medications that typify clinical mental-health care.

Find a brief overview of the most common psychoactive plants employed in ceremonial and medicinal contexts throughout North, Central, and South America on the downloadable PARA/normal Borders Research and Curatorial Overview.

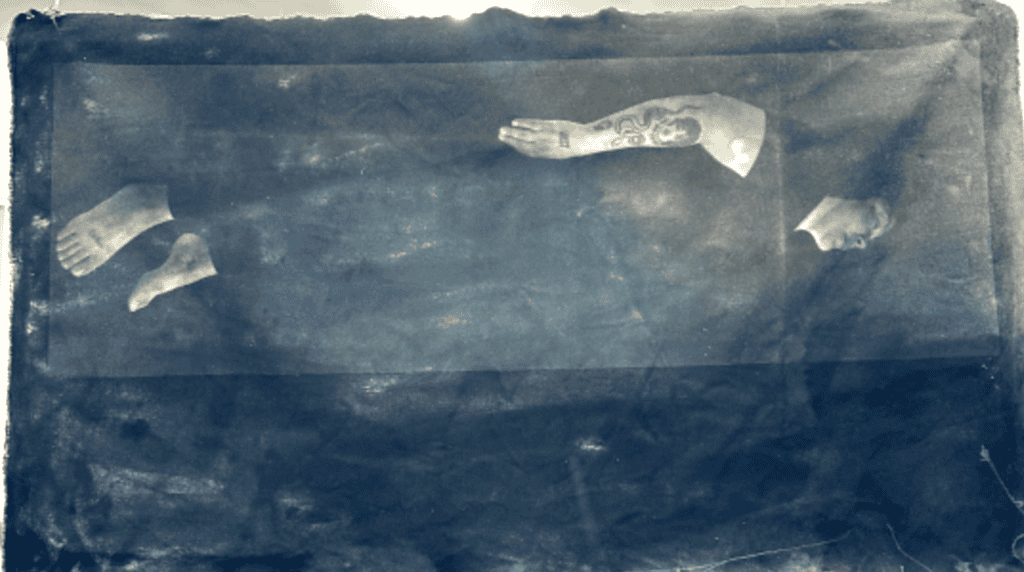

Case Study: Amina Cruz, Sueños

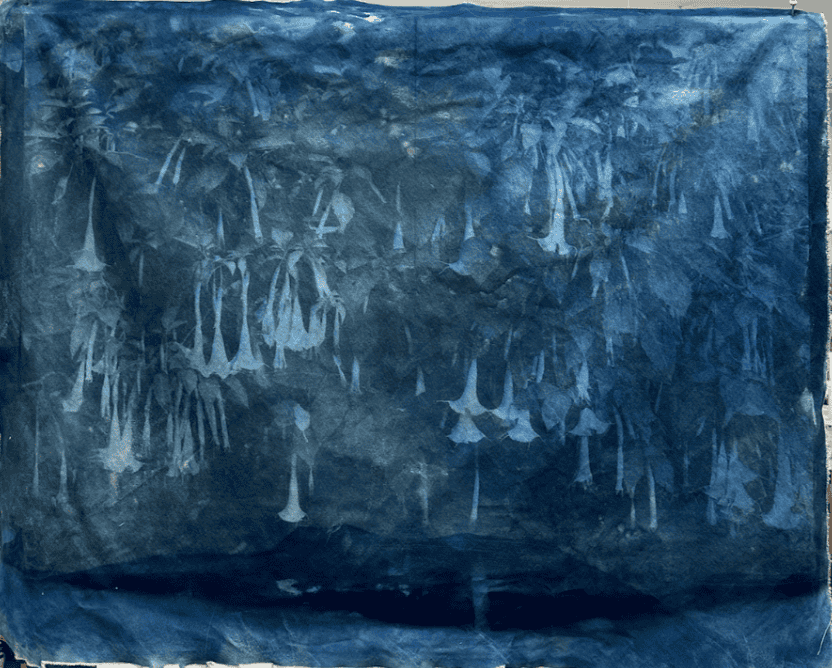

Amina Cruz's cyanotype Sueños (2025) depicts a cascading canopy of angel's trumpet flowers bathed in a sea of murky blue. The dizzying, dreamlike scene mimics the hallucinogenic effects of ingesting the plant. To produce her ethereal cyanotypes, Cruz repeatedly stains her photographs with tea, coffee, and other organic materials. This languid, painstaking undertaking constitutes a ritualized act of spiritual communion in and of itself. Through this alchemical process of staining and obscuration, Amina untethers her photographs from their real-world subjects, creating portals to worlds both eerily familiar and uncanny.

This work was included as part of the exhibition Alma Entre Dos Mundos at the MXCL BNL LAB in Whittier, CA. Find more HERE.

Amina also joined the PARA/normal Borders Podcast to discuss the alchemic process through which she produces her surreal photographs using organic matter. Watch HERE.

Image: Amina Cruz, Sueños, 2025. Cyanotype, tea, and coffee on canvas

Within recent years, the clinical health community’s interest in psychedelics as means of treating various mental illnesses has driven increased research into the integration of spirit medicines into existing healthcare infrastructures. Spirit medicines are typically derived from psychoactive plants, and are imbued with distinct cultural and spiritual meanings. As medical institutions and wellness retreats frame these psychoactive plants as therapeutic tools or personal wellness aids, they sever spirit medicines from the Indigenous governance systems that regulate their use. These industries, furthermore, tend to undercompensate Indigenous healers and educators who provide access to these spirit medicines, if they are consulted in any capacity whatsoever, thereby undermining collective Indigenous practices of stewardship.

Across the Americas, Indigenous and Latine communities rely on community-based healers, such as curanderos and santeros, to provide a holistic form of healthcare which integrates physical, psychological, and spiritual health. Because these healers operate within existing networks of trust and shared social responsibility, the care that they provide is embedded within everyday social life, unlike the contemporary clinical healthcare industry’s reliance on specialized expertise. Some Indigenous academics and health professionals are spearheading collaborative initiatives that seek to integrate spirit medicines into existing healthcare infrastructures without replicating colonial dynamics of extraction, more closely resembling the integrative healthcare provided by community healers. Research into folk illnesses, such as susto, and plant-based treatments demonstrate that these practices are grounded in empirically observable effects, even as they remain articulated through cultural frameworks distinct from settler-colonial medicine.

However, tourism to psychedelic retreats has driven the rapid commercialization of spirit medicines, eroding trust among local Indigenous stakeholders and making it more difficult to implement community-based initiatives of cultural heritage conservation and sustainable tourism development. The exploitative means by which most psychedelic retreats employ Indigenous practitioners and spirit medicines replicate colonial relationships of sociocultural and economic subjugation through appropriation. Ethical engagement with Indigenous systems of collective knowledge within the medical and tourism industries demands reparative frameworks that recognize Indigenous self-determination and decision-making authority while resisting extractivist models of cultural exchange.

Case Study: Fernando Corona, FIELD TRIP

Fernando Corona's FIELD TRIP (2023) is a kaleidoscopic, psychedelic celebration of agricultural labor and ancestral knowledge systems, as much as it is an indictment of borders and the regimes of surveillance and militarism that sustain them. A cannabis plant occupies the center of the composition, with ears of corn emerging from below, and cotton rising above. Corona's inclusion of the three crops vital to Californian agricultural production references the milpa—an Indigenous agricultural practice originating within Maya communities, wherein farmers grow corn, beans, and squash together to form a self-sustaining biodiverse miniature ecosystem. Corona's inclusion of corn here is almost ironic—whereas the Maya grew various corn species, the corn occupying the center of Corona's composition has been genetically modified to prioritize efficiency and high yields. Unlike the standardized, mechanized process of monocultural agriculture that extracts from the land, the milpa is sustained through communal practice and reciprocity with the environment. The drones hovering above the fields symbolize the surveillance regimes that facilitate rapid agricultural production through suppression of workers' autonomy and protection of corporate knowledge.

FIELD TRIP was part of Land of Milk & Honey and was exhibited at The Cheech.

Image: Fernando Corona, FIELD TRIP, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, portable mural

Informed by research in psychology, neuroscience, and consciousness studies, this site turns to Near-Death Experiences (NDEs) and deathbed visions as accounts of threshold perception—experiences that unfold at the border between life and death. While their interpretation remains speculative and resistant to empirical verification, NDEs recur with remarkable consistency across clinical studies and cultural contexts, forming what can be understood as shared phenomenological scripts of liminality.

Subjects in NDE research commonly report a subset of recurring experiences: shifts in visual perspective or out-of-body perception; movement through tunnels or passageways; encounters with intense light or luminous spaces; sensations of serenity, clarity, or release from bodily pain; encounters with nonmaterial beings; panoramic life review; the realization of one’s own death; or the ability to witness scenes occurring beyond the physical body. These experiences often arise during cardiac arrest or other life-threatening events that produce extreme physical or psychological trauma, placing the subject in a state of suspended embodiment.

Rather than interpreting NDEs as evidence of a singular metaphysical truth, PARA/normal Borders approaches them as experiences of crossing without arrival. NDEs occupy a condition of prolonged “almost”—a moment in which consciousness appears to detach from the body without fully departing the world. Like borders, purgatorial states, and detention zones, NDEs are defined by delay, uncertainty, and the reorganization of perception under constraint.

Although numerous theories attempt to explain NDEs neurologically or psychologically, none fully account for the frequency, coherence, or cross-cultural resonance of these reports. While the reality or cause of NDEs remains indeterminate within current scientific paradigms, their persistence points to a deeper question at the center of this project: how perception, identity, and time behave when the boundary between states of being is approached but not crossed. In this sense, NDEs reveal not what lies beyond life, but how consciousness itself is transformed at the border of existence. See also: PARA/bles > The Long Middle

Please refer to Fred Blanco and EJ Massey's episodes of the PARA/normal Border Podcast for near-death experience personal testimonies.

To watch Fred, click HERE.

To watch EJ, click HERE.

Image: Still from Joules of Bizzczar Wormhole Grace Jones The Pretenders and PARA/normal Borders Podcast: EJ Massey, A.K.A. The Legendary Blythe Bizzczar: Music and Madness. In this episode, Massey gives a first-hand account of his near-death experience.

This node synthesizes declassified intelligence research and psychological studies on whether it is possible for human subjects to perceive and describe places, objects, or images without directly observing them with their physical senses. Most of these studies were performed during the Cold War. Their purpose was not to demonstrate psychic phenomena, but to see if human subjects could accurately describe remote or hidden locations, objects, and images without looking at them directly.

In remote viewing and extrasensory perception studies, subjects were often asked to sketch or describe hidden targets while remaining conscious and motionless. According to multiple studies, some descriptions seemed to loosely correspond to details of the targets at rates greater than chance. These descriptions often featured indistinct spatial relationships, shifts in scale or perspective, visual details, and a feeling of intuitively “knowing” rather than rationally determining. Subjects note that these experiences often felt daydream-like, fragmented, and difficult to explain.

However, these findings were largely irreplicable, and when protocols became more rigorous, the results frequently grew weaker or vanished. Moreover, it was hard to distinguish significant correspondences from coincidence, interpretation, and unconscious suggestion. After decades of research, the results were deemed unreliable, and most government remote viewing research was halted.

While the research failed to show that humans could perceive more than they directly sensed, it demonstrates how challenging it is to quantify subjective experience, as well as how badly we want to understand mental function beyond the bounds of direct perception. It serves as an archival record of institutional efforts to systematize and rationalize processes—imagination, perception, and intuition—that defy rational systemization.

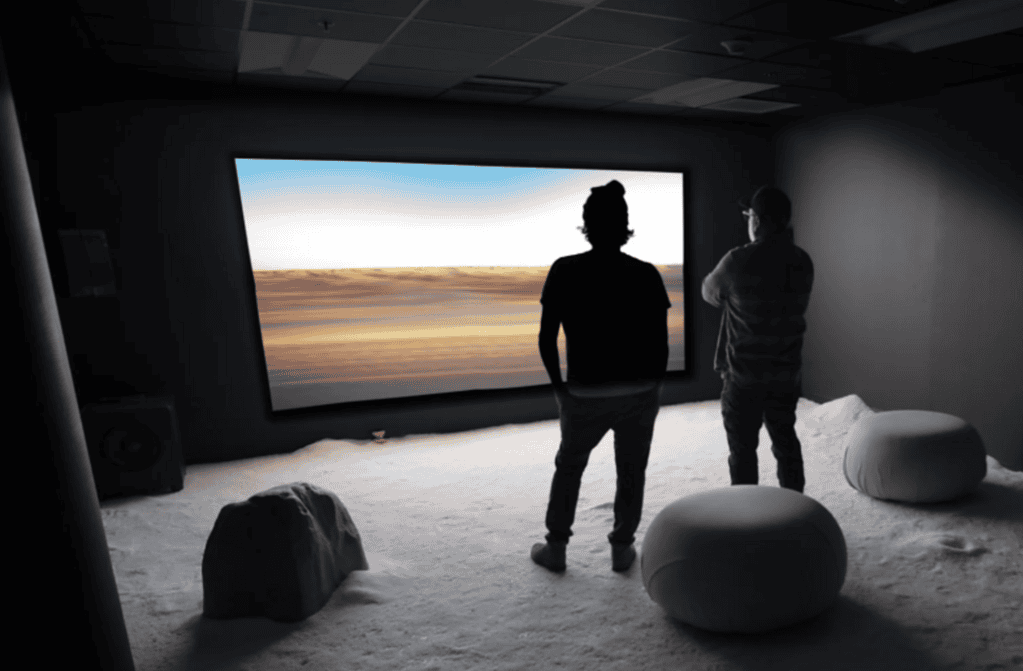

Case Study: Kim Zumpfe, Astral Projections: Yaanga and the not yet

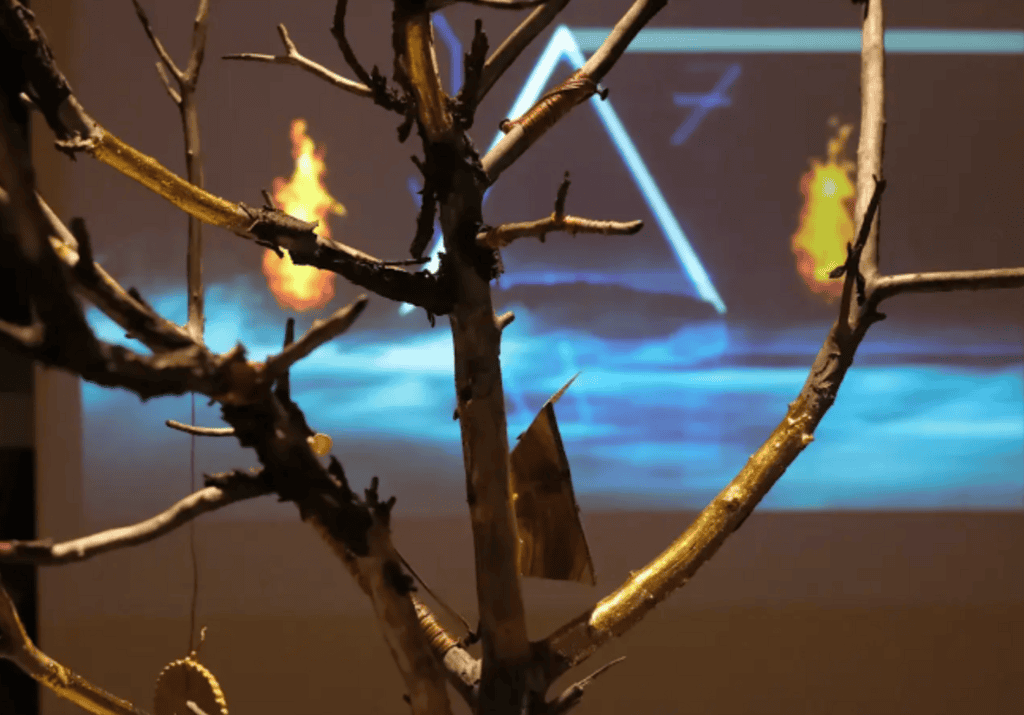

In Astral Projections: Yaanga and the not yet (2019), Kim Zumpfe constructs an installation that examines how perception operates under conditions of destabilized physical and cognitive orientation. Through this, Zumpfe stages a tension between interior subjectivity and external constraint. Partially destroyed architectural elements, locally sourced organic materials, and mediated video imagery produce an environment in which viewers must navigate incomplete visual information and shifting spatial cues. For Zumpfe, perception is shaped as much by absence, obstruction, and inference as by direct sensory input.

This emphasis on perceptual limitation parallels the concerns of Cold War-era remote viewing research, which sought to determine whether subjects could access information regarding a perceptible object without being able to physically perceive it. While those experiments attempted to systematize perception under controlled conditions, Zumpfe’s work situates viewers within the uncertainty such efforts revealed. Moreover, the installation does not suggest the possibility of transcending geopolitical borders or physical embodiment, but explores the psychological and metaphysical means of coping with the limitations that physical restriction and individual embodiment pose, and invites the audience to ponder means of circumventing and subverting these restrictions. In this way, Yaanga and the not yet reflects on the same unresolved question that underpinned remote viewing research: how individuals navigate the gap between what can be sensed, what is inferred, and what ultimately remains inaccessible.

Zumpfe’s Astral Projections: Yaanga and the not yet was part of CALAFIA: Manifesting the Terrestrial Paradise

Image: Kim Zumpfe, Astral Projection: Yaanga and the not yet (2019) Mixed media. MexiCali Biennial CALAFIA: Manifesting the Terrestrial Paradise at the Armory Center for the Arts

Across Indigenous cultures throughout the Americas, ceremonial art serves as a means of maintaining relationships with deities, ancestors, and nonhuman beings. Artmaking often functions as a form of prayer, direct spiritual communion, and offering in and of itself, as creative labor is inseparable from cosmological order. Within these traditions, Indigenous plant knowledge operates as an embodied epistemology: plants are not raw materials or tools, but collaborators and teachers that guide perception, ethics, and artistic process.

Within Wixárika (Huichol) communities of northwestern Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental, this relational knowledge is articulated through the ceremonial deer hunt and the pilgrimage to Wirikuta, the ancestral desert where peyote (hikuri) grows. In Wixárika cosmology, the deer, peyote, and maize form a sacred triad, each reflecting the others across different states of being. The ritual pursuit of the deer is not a hunt in the extractive sense, but a reenactment of origin—a journey that requires fasting, prayer, artistic preparation, and collective discipline. Peyote ingestion during ceremony opens altered perceptual states that allow participants to traverse spiritual thresholds, communicate with ancestors, and receive visions that are later translated into yarn paintings, beadwork, songs, and ritual objects.

Case Study: Isidro Pérez García, Tuleño Guide’s Penacho #1: Michoacán

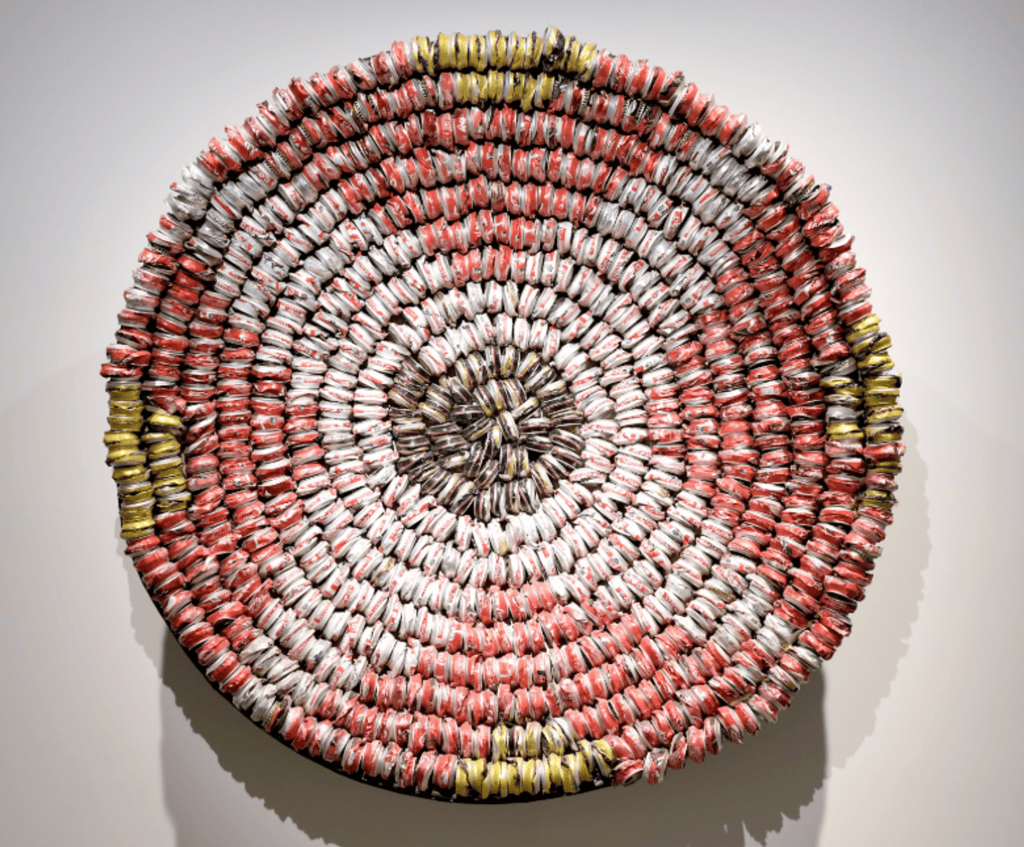

Isidro Pérez García’s penacho series demonstrates how Indigenous plant knowledge and ceremonial practice can be reactivated within mass-produced commercial objects. Here, the baseball cap is a readymade imbued with geopolitical significance, as it is a ubiquitous symbol of globalized production, cultural circulation, and national branding. Pérez García transforms the baseball cap into a site of epistemic negotiation, where ancestral knowledge systems and artistic practices subvert the uniformity of mass-produced objects and confront the commodification of national identity.

In Tuleño Guide’s Penacho #1: Michoacán (2023), the artist affixed long strands of tule to the sides of a snapback baseball cap emblazoned with the word “Michoacán.” The method of tule weaving that Pérez García frequently employs in his work originates from the aforementioned Mexican state, and the strands that sprout from the sides of the baseball cap evoke featherwork found on ceremonial penachos. In this way, Pérez García subverts signifiers of Mexican national identity to question the means by which corporations and nation-states position the nation's resources, its culture, and its people for consumption. The ancient, communal, human-oriented practice of tule weaving is juxtaposed against the contemporary, mechanized, and automated practice of goods production, reorienting the baseball cap as a contested object through which Indigenous knowledge resists extraction and erasure.

Recommended:

“Isidro Pérez García: Terreno Familiar | Familiar Terrain.” Mexicali Biennial Podcast. Mexicali Biennial, 2025. https://mexicalibiennial.org/isidro-perez-garcia-terreno-familiar-familiar-terrain/

This podcast episode features artist Isidro Pérez García discussing his work Terreno Familiar | Familiar Terrain in relation to ancestral land, ecological memory, and the haunting presence of borderlands.

Image: Isidro Pérez García, Tuleño Guide’s Penacho #1: Michoacán, 2023. Tule (gathered from nature reserve), embroidered appliqué baseball cap (cotton & nylon), thread.

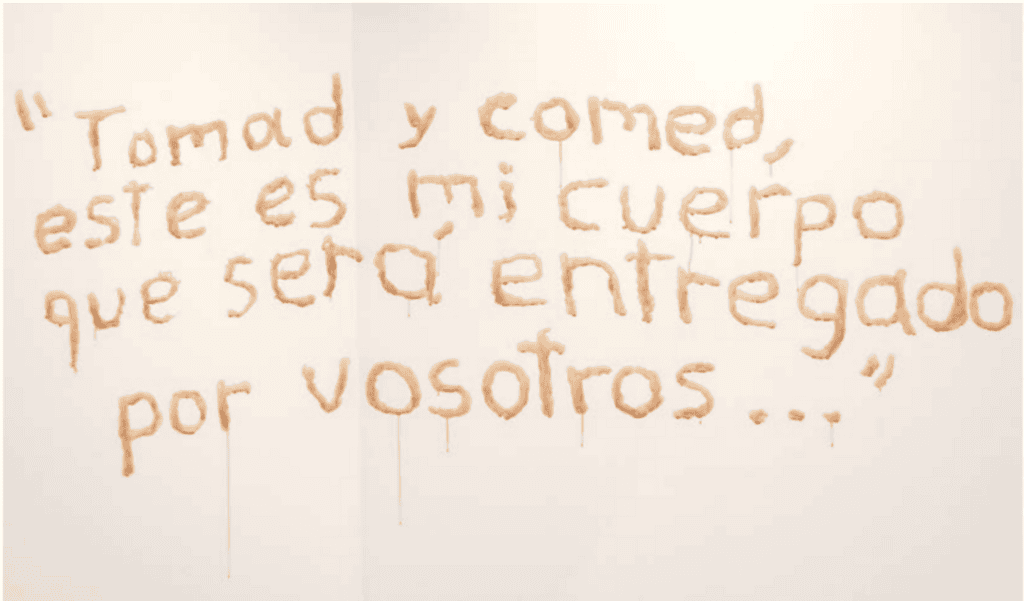

Across cultures, food has been used as a means of communing with the divine, the ancestral, and the everyday. Sacred foods and ceremonial consumption operate as powerful gateways through ritual practices that allow beliefs to move across political, spiritual, and temporal boundaries.

Food carries sacred meaning. The Eucharist transforms bread into the body of Christ, enacting a miracle of presence through consumption. Pan de Muerto bridges the living and the dead, offered during Día de los Muertos. Challah sanctifies time each week, braided into continuity and blessing, while manna—appearing without labor or explanation—functions as divine sustenance. Informal food economies—such as street vending, communal kitchens, and mobile food practices—extend these rituals into public space, transforming everyday acts of feeding into systems of care, cultural preservation, and survival at the margins of regulated economies. Ceremonial consumption also extends beyond food to substances such as tobacco and pulque, which are ingested not for intoxication but for ritual—used in prayer, healing, and to commune with ancestors.

Case Study: Isidro Peréz Garcia, Pulque vs. Chicha: A Chinga-la-Migra Meal

In the summer of 2025, artist Isidro Pérez García created an immersive dinner installation activated by sacred foods and ceremonial consumption as forms of collective resistance. Pulque vs. Chicha: A Chinga-la-Migra Meal centered on fermented beverages with deep ritual histories across the Américas. The gathering unfolded as a three-course, plant-forward meal served in a familial home in Santa Ana, California (Tongva land).

Within the PARA/normal Borders framework, the dinner functioned as a counter-border practice. At a moment marked by heightened immigration enforcement and everyday fear, the act of coming together to eat, drink, and celebrate became a refusal of disappearance. Pérez García framed the meal as a response to raids targeting undocumented communities—communities that have long sustained life, culture, and dignity through informal food economies and shared ritual. The ceremonial consumption of pulque and chicha operated as a defiant act, interrupting fear with presence, joy, and ancestral continuity.

As the second event in the PARA/normal Supper Club series, the gathering extended beyond nourishment into storytelling. Attendees exchanged paranormal encounters, urban legends, and personal histories, transforming the table into a liminal site where memory, survival, and the miraculous circulated together. In this way, the communal event demonstrated how sacred food and drink can operate as a powerful counterpoint to the violent political climate gripping the United States.

Find a non-exhaustive cross-cultural list of Sacred Foods & Ceremonial Consumption on the downloadable PARA/normal Borders Prospectus and Research Overview.

Image: Isidro Peréz Garcia, Pulque vs. Chicha: A Chinga-la-Migra Meal. Flyer and promotional print. PARA/normal Borders Supper Club #2. Ink on paper.

Documentation, archiving, collections, systems, and curatorial storytelling

PARA/text examines the systems that surround, shape, and mediate meaning—documentation, archives, footnotes, written histories, metadata, mapping, curatorial framing, and counter-records—through which knowledge is constructed, authorized, and remembered. The concept draws from literary theorist Gérard Genette, who coined the term paratext to describe the materials that exist “beside the text” (titles, prefaces, captions, institutional framing, images, notes) and that quietly govern how narratives are received, believed, and valued. PARA/text extends this thinking beyond literature into the political, haunted, and speculative terrains.

Topics in this section revolve around systems - databases, registries, permits, maps, missing-person lists, biometric systems, archives, and omissions. These systems decide what becomes visible, what is preserved, and what is allowed to disappear. Archives are never passive. They are haunted structures shaped by surveillance, colonial memory, spiritual practice, ecological rupture, and unresolved loss.

PARA/text foregrounds counter-archives and alternative memory systems—those built outside official institutions through ritual, community mapping, digital experimentation, and curation. It explores how ghosts and hauntologies operate as social records; how digital spirits and generative technologies produce new forms of afterlife; how murals, altars, ex-votos, and ceremonies function as epiphenomenal documents; how mapping becomes a palimpsestic archive; and how spiritual activism and curatorial storytelling intervene where state and academic archives fail.

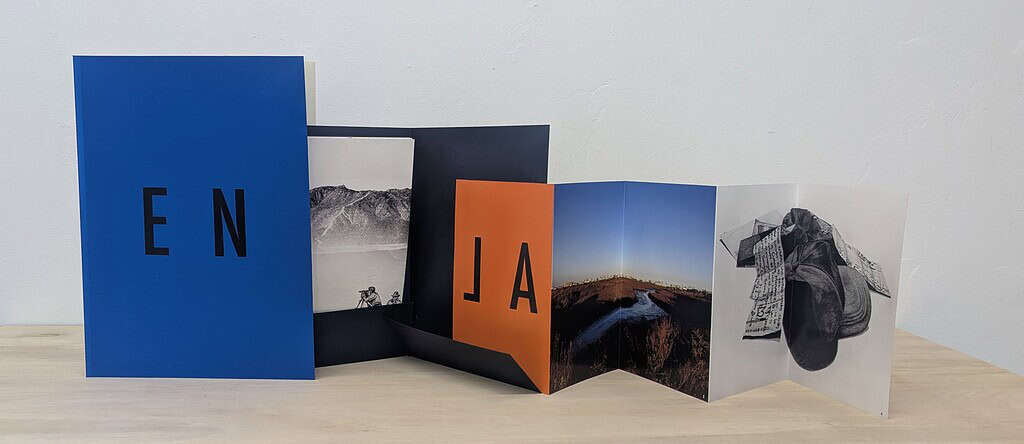

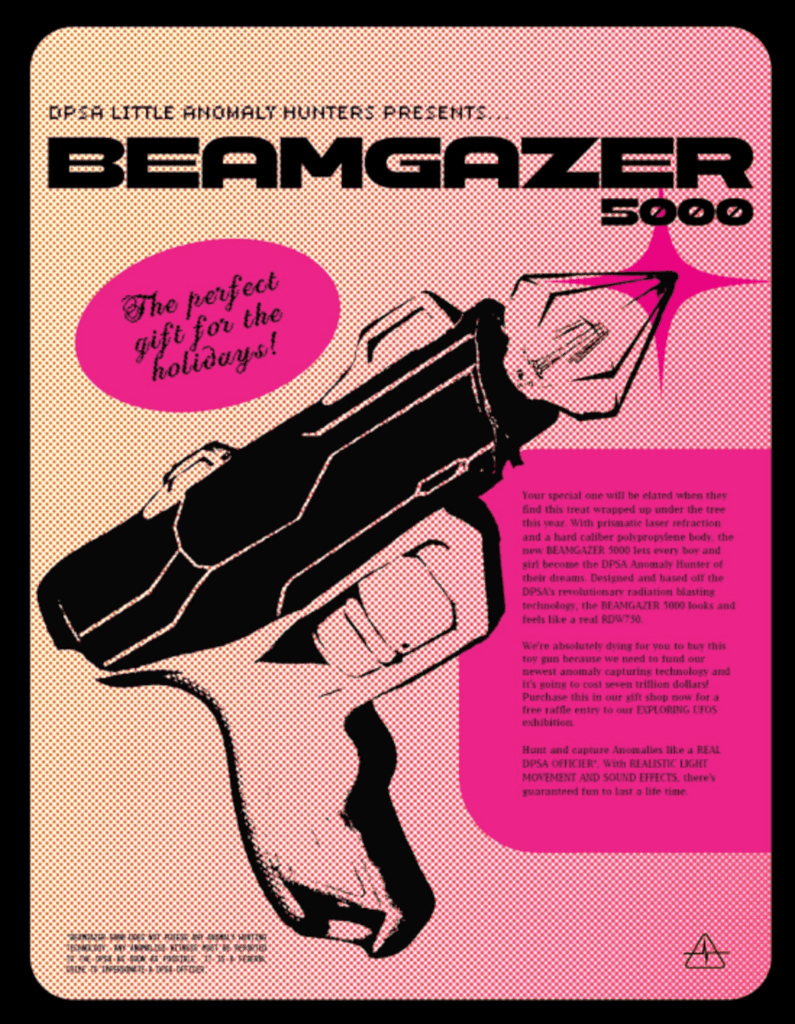

Case Study: ALIEN (Taller California Press)

ALIEN began as an idea “in space,” emerging from the MexiCali Biennial’s PARA/normal Borders Lab as a speculative publishing project that both embodies and interrogates the concept of alienness within and beyond the U.S.–Mexico borderlands. Designed by Taller California with curator Armando Pulido the publication takes the form of a three-book architecture—interlocking yet separable volumes printed in offset, glow-in-the-dark, and Risograph processes. Artists Ed Gómez, Luis G. Hernandez, Lorena Gómez Mostajo, Omar Pimienta, and Jessica Sevilla each produced distinct image series that are pulled apart, recombined, and reorganized. In this way, ALIEN functions as a curatorial archive: a modular documentation system where meaning is produced through assembly, misalignment, and reconfiguration.

The publication situates the term “alien” within overlapping historical registers: from the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, which codified the legal dehumanization of non-citizens, to the science-fiction mythology of Alien (1979), which aestheticized fear of the unknown. Rather than treating “alienness” as extraterrestrial fantasy, the artists excavate terrestrial histories embedded in Baja California and the American Southwest—resource extraction, Indigenous knowledge systems, ecological transformation, and contemporary border enforcement. Through this lens, ALIEN reframes the archive itself as haunted: a site where legal language, pop culture, and material landscapes converge to produce enduring structures of othering.

Within PARA/text, ALIEN operates as a counter-record. Its fragmented structure mirrors the instability of border narratives and exposes how documents, laws, and visual regimes manufacture categories of belonging and exclusion. At the same time, the publication introduces play, glow, and speculative design as archival strategies—suggesting that documentation need not only preserve what has been, but can also prototype new modes of remembering. Here, the book becomes a living system: part archive, part artifact, part world-building device—where curatorial storytelling transforms the publication itself into an epiphenomenon of border histories, carrying both their violence and their potential for reimagining.

ALIEN is the subject of a group exhibition at MXCL BNL LAB titled Alien Excavations, January 31 - March 7, 2026.

ALIEN is available to purchase HERE.

Image: ALIEN book, Taller California and MexiCali Biennial.

Coined by Jacques Derrida, hauntology describes how the present is never fully present. It is always inhabited by unresolved pasts and unrealized futures. Hauntology names the condition in which histories that have been suppressed, denied, or prematurely ended continue to persist.

The ghosts remain.

Along the U.S.–Mexico border, ghosts take many forms. The borderlands are saturated with the afterlives of colonialism, forced displacement, racial violence, cartel terror, femicide, environmental collapse, and unmarked death. The disappeared persist through makeshift shrines, rumors, landscapes, and bureaucratic files. Surveillance towers occupy former ceremonial routes. Migrant trails overlap with ancient trade paths.

The ghosts remember.

Within PARA/normal Borders, hauntology becomes a curatorial method. Curatorial storytelling does not seek to “resolve” the ghost. Instead, it learns to listen. Exhibitions, archives, and public programs become spaces for activating memory, hosting unresolved narratives, and allowing suppressed histories to speak through objects, images, sounds, and bodies. Artists operate as mediums, translating traces into forms that can be felt.

The ghosts are heard.

In this way, curation becomes a practice of haunting. It constructs encounters with what lingers. It treats archives as living systems of return. To curate the border hauntologically is to recognize that every border story is already a ghost story, and that telling it responsibly means building structures where the unseen can remain present.

The ghosts are seen.

Case Study: Chantal Peñalosa Fong, Ghost Stories series

Chantal Peñalosa Fong’s research-based practice unfolds through subtle gestures and quiet interventions that attend to labor, waiting, and temporal suspension. Peñalosa Fong was invited to participate in PARA/normal Borders due to her ongoing Ghost Stories series, a body of work that excavates familial history and ancestral experience in relation to anti-Chinese violence and exclusionary policies of the early twentieth century. These histories—often marginalized within dominant border narratives—resurface in her work not as fixed documentation, but as spectral presences.

Drawing from archival photographs, documents, and personal records, Peñalosa Fong manipulates and reconfigures historical materials to foreground what has been erased, fragmented, or left unresolved. The resulting images operate hauntologically: figures fade, faces blur, and temporal continuity collapses. Rather than restoring the archive, her interventions expose its absences, allowing the past to appear as a series of haunted impressions rather than a stable record.

see also: PARA/noia>desaparecido

Recommended:

“Armando Pulido: Curating Stories.” Mexicali Biennial Podcast. Mexicali Biennial, 2025. https://mexicalibiennial.org/armando-pulido-curating-stories/

This episode features curator Armando Pulido discussing curatorial practice, narrative frameworks, and the politics of storytelling in the context of borderland art and the Mexicali Biennial.

A list of resources examining the ghosts produced by cartel violence and femicide and the stories of disappearance, resistance, and unresolved mourning that continue to haunt the social and psychic landscapes of the borderlands can be found on the downloadable PARA/normal Border Prospectus and Research Overview.

Image: Chantal Peñalosa Fong, Boats. Junks. Photocopies 2, 2023. Silkscreen on linen

Generative ghosts are a form of digital afterlife created through artificial intelligence. Unlike “deadbots,” which are often assembled after someone has died from fragments of public data, generative ghosts are frequently built through intentional pre-death interviews, voice recordings, and curated digital archives, sometimes combined with years of social media activity. They are designed not only to resemble a person, but to continue them—to speak, respond, advise, remember, and even perform tasks after physical death.

Recent research describes a future in which people may leave behind AI agents capable of interacting with descendants, resolving disputes, sharing skills, or maintaining aspects of a person’s social and professional presence. These systems could teach grandchildren family recipes, preserve endangered languages, provide emotional support, or carry forward cultural knowledge. In this sense, generative ghosts are often framed as a form of technological reincarnation. More accurately, they function as reanimations—entities animated by data, trained on traces of a life, and capable of producing new speech beyond their human origin.

Scholars studying “AI afterlives” identify both potential benefits and serious risks. Generative ghosts may offer new modes of remembrance, storytelling, and continuity. They could support grieving families, safeguard testimony, and extend archives into interactive forms. At the same time, they raise profound ethical concerns: the disruption of healthy mourning, emotional dependency, privacy violations, hallucinated memories, posthumous identity theft, and the use of the dead as economic or political instruments. On a societal level, they challenge religious belief systems, destabilize notions of authorship and consent, and blur distinctions between the living, the dead, and the simulated.

Artists have already begun testing this terrain. Laurie Anderson’s AI project based on her late partner Lou Reed approaches generative ghosts not as resurrection, but as stylistic haunting—an exploration of how voice, memory, and creative residue persist through media. Her work foregrounds the instability of these systems: sometimes banal, sometimes uncanny, sometimes unexpectedly resonant.

Within PARA/normal Borders, generative ghosts reveal how haunting is becoming infrastructural. Memory is no longer only archived; it is activated. The dead no longer only linger; they operate. These entities occupy a new border zone - a digital purgatory that asks not only how we remember the dead, but who is permitted to speak for them, and to what ends.

A list of key companies currently providing digital afterlife services can be found on the PARA/normal Borders Prospectus and Research Overview in the "Digital Spirits" section.

see also: PARA/science>AI, Digital Consciousness, and Synthetic Prophets and PARA/science>Deadbots

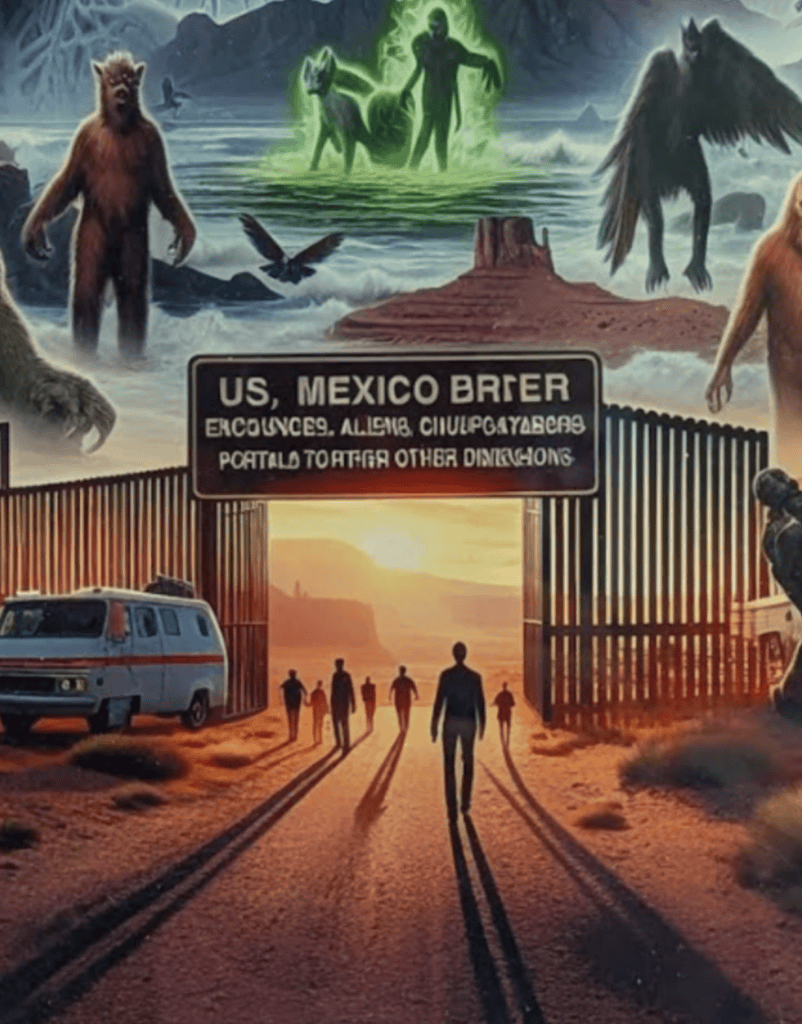

Featured image: This image is part of a series titled PARA/normal Encounters at the Border, consisting of AI-generated images created using the prompt, “What paranormal entities can you encounter at the border between the U.S. and Mexico?” Created by Whittier, CA–based youth Violet Gomez, Sienna Gomez, and Olive Gomez, the project aims to provoke reflection on the metaphysical dimensions of the border. The series is currently installed in the restroom of the MXCL BNL LAB.

This imagery highlights hallucinations that occur within AI programs. Because generative ghosts are built from incomplete archives (texts, images, voice samples, social media traces, interviews), they are not reproductions of a person but probabilistic reconstructions. When they “hallucinate,” they will generate statements, memories, emotions, or advice that were never actually expressed by the deceased.

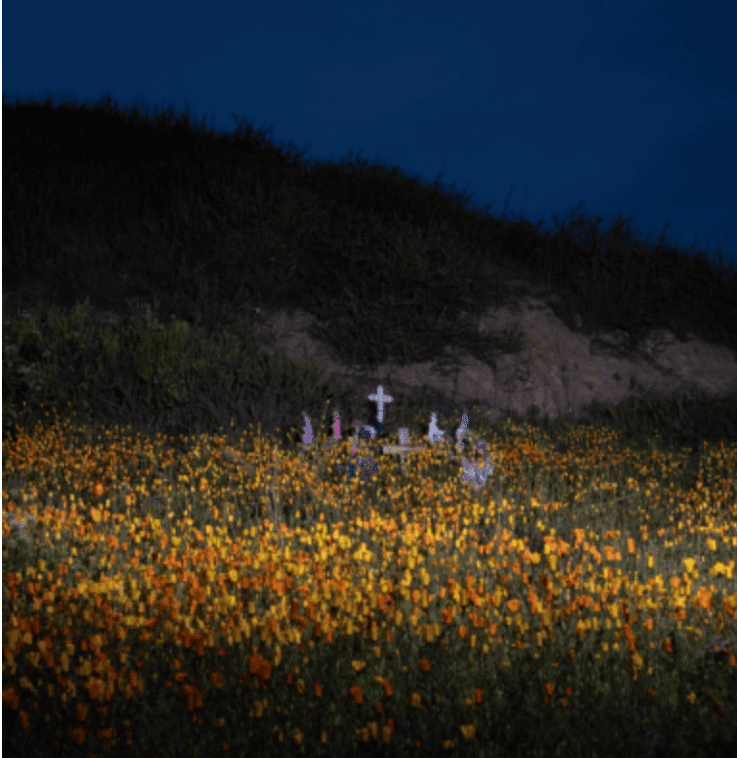

Epiphenomena are secondary, perceptible traces of forces that cannot be fully seen, contained, or measured. They are not the event itself, but what the event leaves behind: residues, gestures, distortions, marks, echoes. Epiphenomena appear when something crosses through a place, a body, a system, or a history. They are the atmospheric evidence of encounters with the unseen, the unresolved, or the unexplainable.

Within PARA/text, ritual documentation focuses on how communities record these traces. Murals, ex-votos, altars, shrines, and offerings function as living archives of epiphenomena. They do not document facts; they document encounters.

Murals can operate as public epiphenomena by marking sites of death or disappearance, territorial memory, spiritual protection, resistance, and collective mourning. The mural is not the event. It is the imprint of the event on the social atmosphere, a visual residue that insists something happened here.

Likewise, ex-votos are created after survival, crisis, healing, or miracle. They record encounters with danger, divine or paranormal intervention, and gratitude after rupture. Each ex-voto becomes a micro-archive of the miraculous: evidence of something that cannot be empirically proven but must be remembered.

Altars and shrines function as spatial epiphenomena. They emerge where institutions fail: where bodies were not recovered, where justice did not arrive, where grief required form, where belief needed grounding. Candles, photographs, shoes, rosaries, water bottles, toys, handwritten notes are not symbols. They are residues of lived relationships with absence and presence.

Ritual documentation recognizes these practices as curatorial acts. Altars are curated traces. Murals are public memory systems. Ex-votos are narrative data. Together, they reveal how communities archive what official systems cannot hold.

Case Study: Adrián Pereda Vidal, Sonic Meditations: Synthesizing the Supernatural

Adrián Pereda Vidal’s Sonic Meditations: Synthesizing the Supernatural transforms the MXCL BNL LAB into a site of ritual documentation. The installation consists of three distinct soundworks that play simultaneously, saturating the space with layered frequencies that shift as visitors move through the gallery. Rather than presenting a single narrative or image, the work creates an immersive field in which perception itself becomes the medium.

Sonic Meditations, which was curated by Sam Romo-White, is structured around epiphenomena: the subtle traces of something that cannot be directly seen. The artist draws from familiar paranormal experiences—an unexplained sound, a sudden silence, a feeling of presence—to propose sound as evidence rather than event. What visitors encounter are not representations of the supernatural, but its residues: vibrations, reverberations, and atmospheric disturbances that suggest an elsewhere without defining it.

As the soundworks modulate, synthesized graphics projected onto the gallery walls respond in real time, producing visual epiphenomena of the sonic environment. These shifting forms function as a secondary layer of documentation, translating invisible forces into perceptible traces. Pereda Vidal’s project demonstrates how ritual documentation can archive what resists capture. Here, the border between sound and space, presence and absence, becomes porous, and epiphenomena emerge as the primary record of an encounter with the unseen.

Image: Adrian Pereda Vidal, Sonic Meditations: Synthesizing the Supernatural, 2025. Projection and Audio

Mapping is often understood as a tool for orientation or control. It can also be approached as an archival act. Every map records more than geography; it documents movement, power, memory, and erasure. To map is to collect traces of how a place has been lived, crossed, renamed, governed, imagined, and resisted. In this sense, maps operate as living archives—storing not only what is visible, but what has been buried, displaced, or rendered illegible.

Like a surface written on, erased, and written over again, landscapes carry multiple inscriptions at once. Indigenous trade routes persist beneath colonial borders. Ancient waterways echo under canals and pipelines. Ceremonial grounds survive beneath military zones. Migrant paths run alongside highways. Each new map overlays earlier ones without fully erasing them. The past remains as residue, distortion, and haunting. When artists and curators map the borderlands, they are not producing new images of empty space, but activating layered records of historical, ecological, and spiritual presence.

As an archival practice, mapping gathers fragments: oral histories, satellite images, testimonies, ruins, sensor data, sacred sites, rumors, and routes. These materials form counter-archives that challenge official cartographies, which often present territory as neutral, stable, and singular. Counter-mapping instead foregrounds multiplicity. It charts what state maps omit: disappearance zones, informal crossings, ancestral geographies, ecological collapse, and speculative futures.

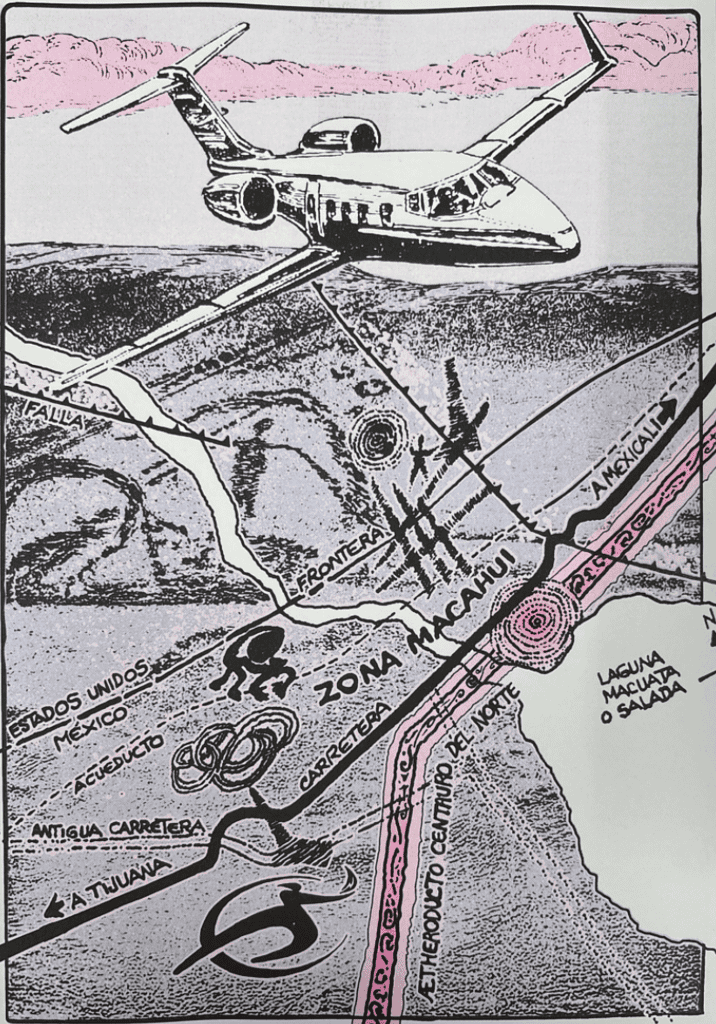

Case Study: Jessica Sevilla, Geometrías de La Duda (ALIEN book contribution)

Mexicali-based artist and researcher Jessica Sevilla works with mapping as a speculative and archival practice. After encountering issue No. 590 of La Duda (The Doubt)—which documented stone circles and geoglyphs found in 1977 at a site called Macahui, linked to ancient Lake Cahuilla—Sevilla began intervening the magazine’s images with her own photographs and drawings. These additions layer ancestral geometries with contemporary infrastructures such as aqueducts and gas pipelines, creating counter-maps where ancient waters, colonial extraction, and speculative futures coexist.

Rather than fixing territory, Sevilla treats mapping as a palimpsest: a living archive of doubt, memory, and more-than-human presence. Her work reveals how landscape holds overlapping histories that cannot be contained by scientific or political cartography alone.

This project is Sevilla’s contribution for ALIEN, a small-run artist book created by Taller California for the MexiCali Biennial.

About ALIEN:

ALIEN is a multi-part artist publication that brings together five artists to investigate the meaning of “alienness” within the U.S.–Mexico borderlands through three interlocking books produced with Taller California and MexiCali Biennial. Rather than looking to outer space, the artists turn toward the land itself, surfacing buried histories of extraction, migration, and Indigenous memory to reveal how colonial and imperial systems have rendered both people and environments “alien.” Accompanied by the exhibition Alien Excavations at the MXCL BNL LAB (January 31–March 7, 2026), the project reframes science fiction as a critical tool for confronting the past and imagining more just futures.

ALIEN is available for purchase HERE.

Image: Jessica Sevilla, Geometrías de La Duda (ALIEN book contribution). Risograph print.

Archival sequencing refers to the curatorial and artistic practice of arranging documents, images, objects, and records in ways that produce new meaning. Rather than treating the archive as a neutral repository of facts, archival sequencing understands it as an active narrative system—one that shapes how histories are perceived, remembered, and believed. What is placed next to what, what is repeated, what is omitted, and what is allowed to glow all determine how the past is assembled in the present.

Within PARA/normal Borders, archival sequencing becomes a method for revealing how borders are not only enforced through walls and policies, but through images, rumors, scientific illustrations, maps, photographs, and bureaucratic traces. When artists reorganize these materials, they expose the archive’s instability.

Archival sequencing also allows the paranormal to enter documentation. A postcard becomes prophecy. An illustration becomes an omen. A photograph becomes a trace of something unfinished. Through deliberate montage and juxtaposition, artists transform records into epiphenomena—perceptible residues of events, forces, and systems that exceed what official histories can contain.

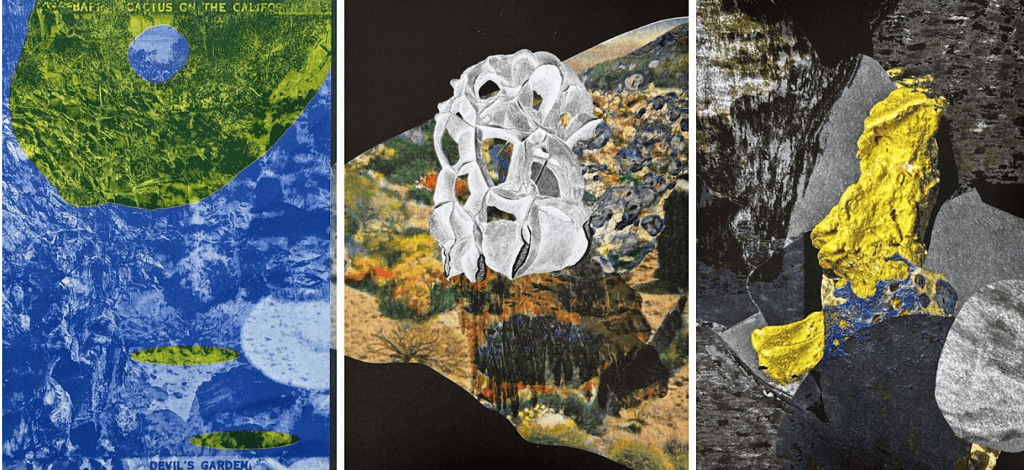

Case Study: Lorena Gomez Mostajo, Gold Rush

Lorena Gomez Mostajo’s Gold Rush operates as an act of archival sequencing, assembling a fragmented visual narrative around the brief nineteenth-century gold rush in Baja California and its long afterlife. The project moves between expedition photography, scientific illustrations of quartz formations, desert postcards, and the image of the “Boot of Cortez,” the largest gold nugget ever found in North America. Rather than reconstructing a linear history, Gomez Mostajo arranges these materials to echo one another across time—allowing rumor, extraction, speculation, and fantasy to circulate as parallel forces.

By sequencing archival fragments from different eras, Gold Rush exposes how imperial desire, scientific imagery, and commercial mythologies converge to shape territorial imagination. The glowing quartz, tinted landscapes, and isolated objects function less as evidence than as residues—epiphenomena of a larger extractive logic that continues to structure the borderlands. The archive becomes atmospheric, suggesting how the pursuit of wealth leaves behind not only economic traces, but visual and psychic ones.

Gold Rush is included in the publication ALIEN (Taller California Press), where the project participates in a broader interrogation of “alienness” as a category historically used to name both the unknown and the unwanted. Within the book’s nonlinear, three-volume architecture, Gomez Mostajo’s images extend the publication’s examination of how fear, desire, and otherness are embedded in visual systems—from colonial law to science fiction. In this context, Gold Rush positions extraction itself as an alien force: one that reorganizes land, bodies, and belief through speculative promise.

About ALIEN:

ALIEN is a multi-part artist publication that brings together five artists to investigate the meaning of “alienness” within the U.S.–Mexico borderlands through three interlocking books produced with Taller California and MexiCali Biennial. Rather than looking to outer space, the artists turn toward the land itself, surfacing buried histories of extraction, migration, and Indigenous memory to reveal how colonial and imperial systems have rendered both people and environments “alien.” Accompanied by the exhibition Alien Excavations at the MXCL BNL LAB (January 31–March 7, 2026), the project reframes science fiction as a critical tool for confronting the past and imagining more just futures.

ALIEN is available for purchase HERE.

See also: PARA/dise > Ghost Towns for more information on extraction in relation to PARA/normal Borders.

Image: Lorena Gomez Mostajo, from the Gold Rush series (ALIEN book). Risograph print.

In an era increasingly defined by political interference in cultural expression, Spiritual Activism offers a curatorial strategy grounded in the transmission of meaning beyond the fraught boundaries of institutional control. Rooted in Gloria Anzaldúa’s conocimiento—a spiritual practice that bridges inner, personal work and outward, public action—this approach positions curation as a site where transformation, ethics, and imagination converge. Within PARA/normal Borders, the paranormal is not treated as spectacle, but as a culturally flexible spirituality that opens portals to insights suppressed by dominant epistemologies.

Spiritual Activism asks: what do we do with the knowledge we encounter? In curatorial practice, this knowledge becomes a tool for social change, activated through relationships of care, collective reflection, and ethical accountability. The accumulation of research—understood here as a creative act in itself—is filtered through conocimiento: a way of seeing that emerges from critical encounter, experiential wisdom, and personal reflection.

These strategies are especially urgent at a moment when cultural institutions are under pressure—politically, financially, and ideologically—to sanitize and restrict expression. Recent federal reviews and policy threats aimed at artifacts, exhibitions, and institutional autonomy risk silencing voices and narrowing public discourse. Artists have withdrawn work in protest of censorship; the resignation and dismissal of curators reveal not isolated incidents, but a broader assault on free expression and institutional independence.

Anzaldúa describes conocimiento as something achieved through creative acts—writing, art-making, healing, and teaching—that move individuals beyond binary, black-and-white thinking. In these “paranormal” times, Spiritual Activism reasserts the arts as essential infrastructure: not ancillary, but central to civic life, critical inquiry, and social resilience. As a curatorial strategy—and itself a creative act—it mobilizes the unseen and the felt, drawing on soft power to resist erasure, uphold free expression, and cultivate transformative experiences that extend far beyond the gallery walls.

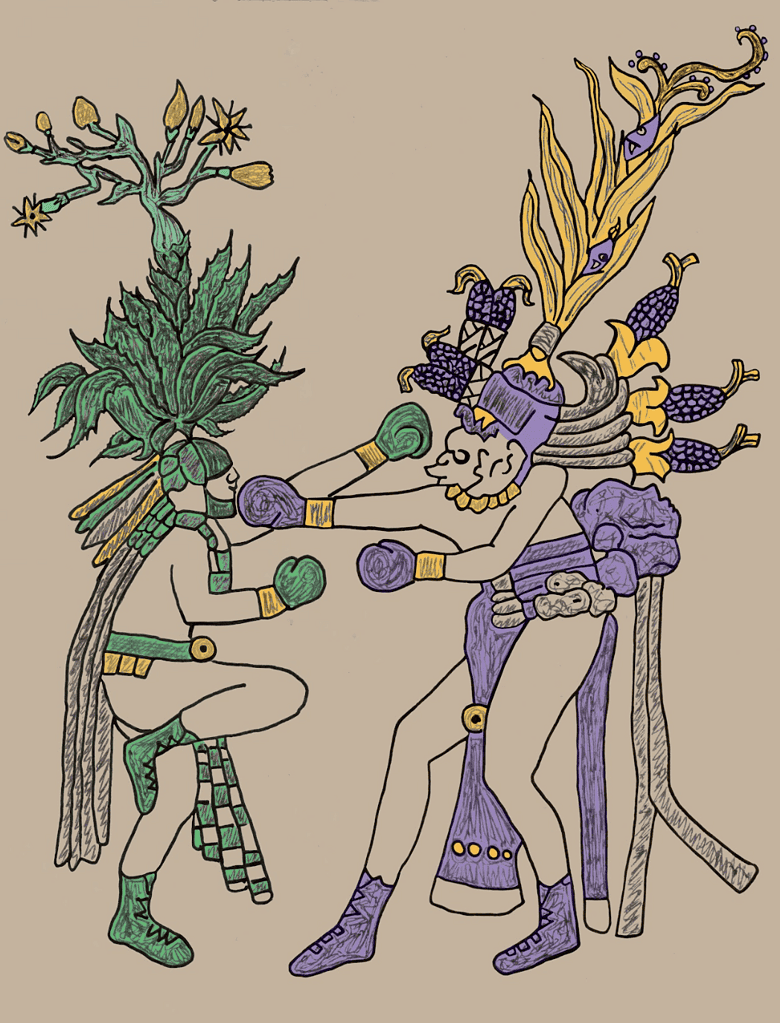

Case Study: Liliana Conlisk Gallegos (Mystic Machete), Before the Sixth Sun: A Codex For Our Children